Map Snapshot

100 Records

Status

"Naturalized from Europe; Labrador to Alaska, and southward" (Reed, 1964).

Description

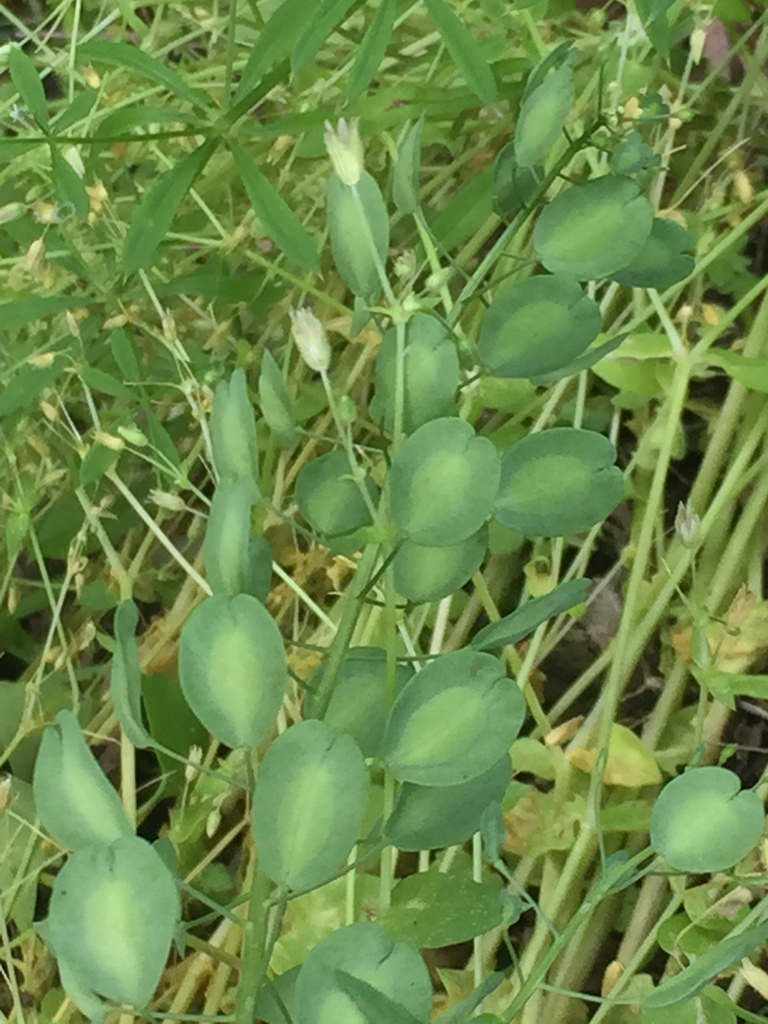

Stem is hairless; stalked basal leaves; stem leaves slightly clasping. Does not smell strongly of garlic. Compare recently established Roadside Pennycress, which is not treated in most popular Eastern U.S. wildflower guides.

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Thlaspi arvense | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Brassicales |

| Family: | Brassicaceae |

| Genus: | Thlaspi |

| Species: | T. arvense

|

| Binomial name | |

| Thlaspi arvense | |

Thlaspi arvense, known by the common name field pennycress,[1] is a flowering plant in the cabbage family Brassicaceae. It is native to Eurasia, and is a common weed throughout much of North America and its home.

Description

[edit]Thlaspi arvense is a foetid, hairless annual plant, growing up to 60 cm (24 in) tall,[2] with upright branches. The stem leaves are arrow-shaped, narrow and toothed. It blooms between May and July, with racemes or spikes of small white flowers that have 4 sepals and 4 longer petals.[3] Later it has round, flat, winged pods with a deep apical notch,[2]: 141 measuring 1 cm (0.39 in) across. They contain small brown-black seeds.[3]

The common name 'pennycress' is derived from the shape of the seeds looking like an old English penny.[3] Other English common names are: stinkweed, bastard cress, fanweed, field pennycress, frenchweed and mithridate mustard. Pennycress is an annual, overwintering herb with an unpleasant odor when its leaves are squeezed. It grows up to 40 to 80 cm depending on environmental conditions. White, lavender or pink flowers with four petals develop between five and eight seeds. Numbers of chromosomes is 2x.[4] Pennycress, has flat and circular notched pods. Its seeds have a high oil content and the species has gained interest as a potential feedstock for biofuel production.

Morphology

[edit]Pennycress is planted and germinates in the fall and overwinters as a small rosette.[5] The central stem and upper side stems terminate in erect racemes of small white flowers. Flowers are self-pollinated and produce a penny sized, heart-shaped, flat seed pod with up to 14 seeds. Each dark brown seed is oval-shaped and slightly larger than a camelina seed (Camelina sativa).[6] Pennycress grows as a winter annual across much of the Midwestern US and the world.[5]

Distribution

[edit]The field pennycress is native to the temperate regions of Eurasia, in many of which it is an archaeophyte (an ancient introduction). It has been naturalised to North America, and so can be regarded as having a circumpolar distribution.[7]

It is found throughout Europe (it is missing from Iceland, the Faroese and Svalbard, relatively rarer in the Arctic and the Mediterranean mainlands, and absent from Portugal and the Mediterranean islands).[8][9] Its area then extends through the Greater Caucasus, the Armenian Highlands, northwestern Iran, Kazakhstan, southern Siberia and up to the Pacific coast of Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krai, the Altai, Tian Shan and Pamir mountains, Korea and the Japanese Archipelago,[10] all but the southeasternmost provinces of China,[11] the mountains in the north of South Asia[10] (in parts of Nepal at 2000–4600 m,[12] in Indian Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, in Pakistan's Chitral, Hazara, Kurram Valley, and as far south as Rawalpindi District),[13] and Ethiopia.[10]

It has also been introduced to Australia and the Americas.[11] In the northern parts of the United States, its habitats include cropland, fallow fields, areas along roadsides and railroads, gardens plots, weedy meadows, and waste areas. This plant prefers disturbed areas, and its capacity to invade higher quality natural habitats is low.[6]

Climate requirements

[edit]Pennycress grows well in many different climates. It can produce seeds in the northern hemisphere during the winter season. In the US and the Mediterranean it is sown commonly in October and can be harvested in May/June. To reach its yield potential a precipitation of about 300mm is needed.[14] Pennycress has a rather low water use efficiency needing 405 litres of water to produce 0.45kg of seeds.[15] Limited water availability depresses the yield. In general, pennycress is not well adapted for arid environments without irrigation.[16]

Ecology

[edit]Field pennycress is a weed of cultivated land and wasteland.[9] A study in Germany indicates that a pennycress-corn double-cropping system improves spider diversity to a larger degree than mustard-corn, green fallow-corn and bare fallow-corn double cropping systems.[17] The addition of pennycress to a corn rotation also increased and stabilized ground beetle diversity more effectively than a mustard (Sinapis alba)–corn rotation, a green fallow–corn rotation, or a bare fallow–corn rotation. This was mainly due to the evenness of plant cover throughout the growing season. Therefore, Bioenergy from double-cropped pennycress may support ground beetle diversity.[17]

Pennycress can be utilized as part of a comprehensive integrated weed management strategy.[18] Fall establishment can provide early spring ground cover and suppress aggressive spring germinating weeds such as common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album), giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida), and tall waterhemp (Amaranthus tuberculatus).[18] Johnson et al. (2015) speculated that weed suppression may have been caused by allelopathic compounds rather than ground cover when pennycress seeding rates and companion crops were taken into account.[18]

Agronomy

[edit]Seeding

[edit]Current studies suggest a seeding rate of 1500 seeds per meter square for Europe while 672 seeds per meter square is suggested for the US. This variability is due to different climates.[4] The recommended seeding depth is around 1 cm. For good germination rates pennycress needs about 25-40mm of water and favours cold and wet conditions.[15]

Fertilization

[edit]In order to increase yields several studies evaluated the effect of fertilization on pennycress. Generally cover crops like pennycress are used to take up the available nutrients to prevent them from leaching. Nitrate and sulphur fertilization had positive effects on the seed yield of pennycress, but also no fertilized treatments showed sufficient[clarification needed] yields.[15]

Harvesting yield

[edit]Pennycress can be harvested with common machinery used for grain/corn and soy bean production. This makes it favorable for integration in many crop rotations. As pennycress is grown over the winter period the combines for harvesting are available in spring time as the harvest of all other crops happens at a different time of the year. The seed yield ranges for pennycress grown as a production crop currently range from 1000 kg/ha to 1500 kg/ha [19]

Integration in soy maize crop rotations

[edit]In the mid east of the US a common crop rotation is Soybean and Maize. After harvest the fields are kept as fallows. Pennycress appears to be especially well suited for oil production when cultivated before soybean. As a cover crop grown over the winter period with harvest taking place in spring, it can effectively reduce soil erosion, prevent nutrient leaching, improve soil structure and increase biodiversity.[17][14] The required machinery for cultivation is already available in the region, as it is the same used for maize and soybean production.[4] In the Mid-western United States, its use as a rotation crop with soybean and maize maintains the pathogen Soybean Cyst Nematode (Heterodera glycines), though less effectively than other legumes[20]

Uses

[edit]Oil

[edit]The first attempts to grow pennycress as an oil crop took place in 1994. However, since 2002 it is more and more considered as a potential oil crop rather than a “noxious weed”.[4] High erucic acid content (>300g per kg of its total seed oil DM) makes the oil from landraces unsuitable for food purposes. Pennycress landraces also contain Glucosinolates, which make the usage as food undesirable.[4] Recently pennycress oil has attracted great interest as raw material for jet fuel and Biodiesel production.[21] Oils with high erucic acid are especially suitable for jet fuel production.[22] Oil characteristics are highly influenced by specific environmental conditions such as precipitation.[4]

Feed

[edit]Due to the high erucic acid content the seeds are unsuitable for human consumption. Instead, the biomass can be used as feed for livestock. Its fast growth under cold conditions favors the usage as fodder as a second crop.[4] Its low biomass production makes it undesirable to concentrate on pennycress cultivation for fodder production.

Food

[edit]The field pennycress has a bitter taste; it is usually parboiled to remove the bitter taste. This is mostly used in salads, sometimes in sandwich spreads. It is said to have a distinctive flavour.[23]

Use as a source of biodiesel

[edit]Pennycress is being developed as an oilseed crop for production of renewable fuels.[24][25] The species can be planted in the fall, will germinate and form a vegetative mass which can overwinter. In the spring, the oil-rich seed can be harvested and used as a biodiesel feedstock.

Research

[edit]Pennycress is related to the model plant species Arabidopsis thaliana. Researchers have begun studying the genetics of pennycress in order to improve its potential use as a biofuel crop. For example, the transcriptome of pennycress has been sequenced.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ NRCS. "Thlaspi arvensis". PLANTS Database. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b Stace, C. A. (2010). New Flora of the British Isles (3rd ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-70772-5.

- ^ a b c Reader's Digest Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain. Reader's Digest. 1981. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-276-00217-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zanetti, Federica; Isbell, Terry A.; Gesch, Russ W.; Evangelista, Roque L.; Alexopoulou, Efthymia; Moser, Bryan; Monti, Andrea (November 2019). "Turning a burden into an opportunity: Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense L.) a new oilseed crop for biofuel production". Biomass and Bioenergy. 130: 105354. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2019.105354. S2CID 204123315.

- ^ a b Isbell, Terry A. (15 July 2009). "US effort in the development of new crops (Lesquerella, Pennycress Coriander and Cuphea)". Oléagineux, Corps Gras, Lipides. 16 (4–5–6): 205–210. doi:10.1051/ocl.2009.0269.

- ^ a b Phippen, W.B.; Phippen, M.E. (2013). Seed Oil Characteristics of Wild Field Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense L.) Populations and USDA Accessions (PDF). Association for the Advancement of Industrial Crops 25th Annual meeting. Washington DC USA.

- ^ Hultén, Eric; Fries, Magnus (1986). Atlas of North European vascular plants north of the Tropic of Cancer. Vol. III. Koeltz Scientific. p. 1063. ISBN 3874292614.

- ^ Jalas, J.; Suominen, J.; Lampinen, R. (1996). Atlas Florae Europaeae. Distribution of Vascular Plants in Europe. Vol. 11. Cruciferae (Ricotia to Raphanus). Helsinki: The Committee for Mapping the Flora of Europe & Societas Biologica Fennica Vanamo. p. 143. ISBN 951-9108-11-4.

- ^ a b "Online Atlas of the British & Irish flora: Thlaspi arvense, Field pennycress". London, U.K.: Biological Records Centre and Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 29 May 2016. [For details of distribution on the British Isles.]

- ^ a b c Meusel, Hermann; Jäger, E.; Weinert, E. (1965). Vergleichende Chorologie der zentraleuropäischen Flora. Vol. [Band I]. Jena: Fischer. K179.

- ^ a b "Thlaspi arvense Linnaeus". Flora of China. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Thlaspi arvense L." Flora of Nepal. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Thlaspi arvense L." Flora of Pakistan. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b Moore, Kenneth J; Karlen, Douglas L (9 April 2014). "Double cropping opportunities for biomass crops in the north central USA". Biofuels. 4 (6): 605–615. doi:10.4155/bfs.13.50. S2CID 56004605.

- ^ a b c Cubins, Julija A.; Wells, M. Scott; Frels, Katherine; Ott, Matthew A.; Forcella, Frank; Johnson, Gregg A.; Walia, Maninder K.; Becker, Roger L.; Gesch, Russ W. (4 September 2019). "Management of pennycress as a winter annual cash cover crop. A review". Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 39 (5). doi:10.1007/s13593-019-0592-0.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Royo-Esnal, Aritz; Edo-Tena, Eva; Torra, Joel; Recasens, Jordi; Gesch, Russ W. (January 2017). "Using fitness parameters to evaluate three oilseed Brassicaceae species as potential oil crops in two contrasting environments". Industrial Crops and Products. 95: 148–155. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.10.020. hdl:10459.1/59125.

- ^ a b c Groeneveld, Janna H.; Lührs, Hans P.; Klein, Alexandra-Maria (August 2015). "Pennycress double-cropping does not negatively impact spider diversity". Agricultural and Forest Entomology. 17 (3): 247–257. doi:10.1111/afe.12100. S2CID 82895391.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Gregg A.; Kantar, Michael B.; Betts, Kevin J.; Wyse, Donald L. (2015). "Field Pennycress Production and Weed Control in a Double Crop System with Soybean in Minnesota". Agronomy Journal. 107 (2): 532. doi:10.2134/agronj14.0292. S2CID 4945325.

- ^ "IPREFER project www.iprefercap.org"

- ^ Hoerning, Cody; Chen, Senyu; Frels, Katherine; Wyse, Donald; Wells, Samantha; Anderson, James (2022). "Soybean Cyst Nematode Population Development and Its Effect on Pennycress in a Greenhouse Study". Journal of Nematology. 54. doi:10.2478/jofnem-2022-0006. PMID 35860521.

- ^ Sindelar, Aaron J.; Schmer, Marty R.; Gesch, Russell W.; Forcella, Frank; Eberle, Carrie A.; Thom, Matthew D.; Archer, David W. (March 2017). "Winter oilseed production for biofuel in the US Corn Belt: opportunities and limitations". GCB Bioenergy. 9 (3): 508–524. doi:10.1111/gcbb.12297.

- ^ Nieschlag, H. J.; Wolff, I. A. (November 1971). "Industrial uses of high erucic oils". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 48 (11): 723–727. doi:10.1007/BF02638529. S2CID 43546307.

- ^ "Field Pennycress Thlaspi arvense". ediblewildfood.com. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ CoverCress, Inc. website

- ^ Field pennycress shows feedstock potential

- ^ Dorn, Kevin M.; Fankhauser, Johnathon D.; Wyse, Donald L.; Marks, M. David (September 2013). "De novo assembly of the pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) transcriptome provides tools for the development of a winter cover crop and biodiesel feedstock". The Plant Journal. 75 (6): 1028–1038. doi:10.1111/tpj.12267. PMC 3824206. PMID 23786378.