Map Snapshot

38 Records

Status

Glabrous whitish pileus, sometimes darkening with a rosy color. Taste is acrid. White latex slowly turns yellow when exposed to the air. (L. Biechele, pers. comm.)

Relationships

Associated with oaks.

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Lactarius chrysorrheus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Russulales |

| Family: | Russulaceae |

| Genus: | Lactarius |

| Species: | L. chrysorrheus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lactarius chrysorrheus | |

| Lactarius chrysorrheus | |

|---|---|

| Gills on hymenium | |

| Cap is flat or depressed | |

| Hymenium is decurrent | |

| Stipe is bare | |

| Spore print is cream | |

| Edibility is poisonous | |

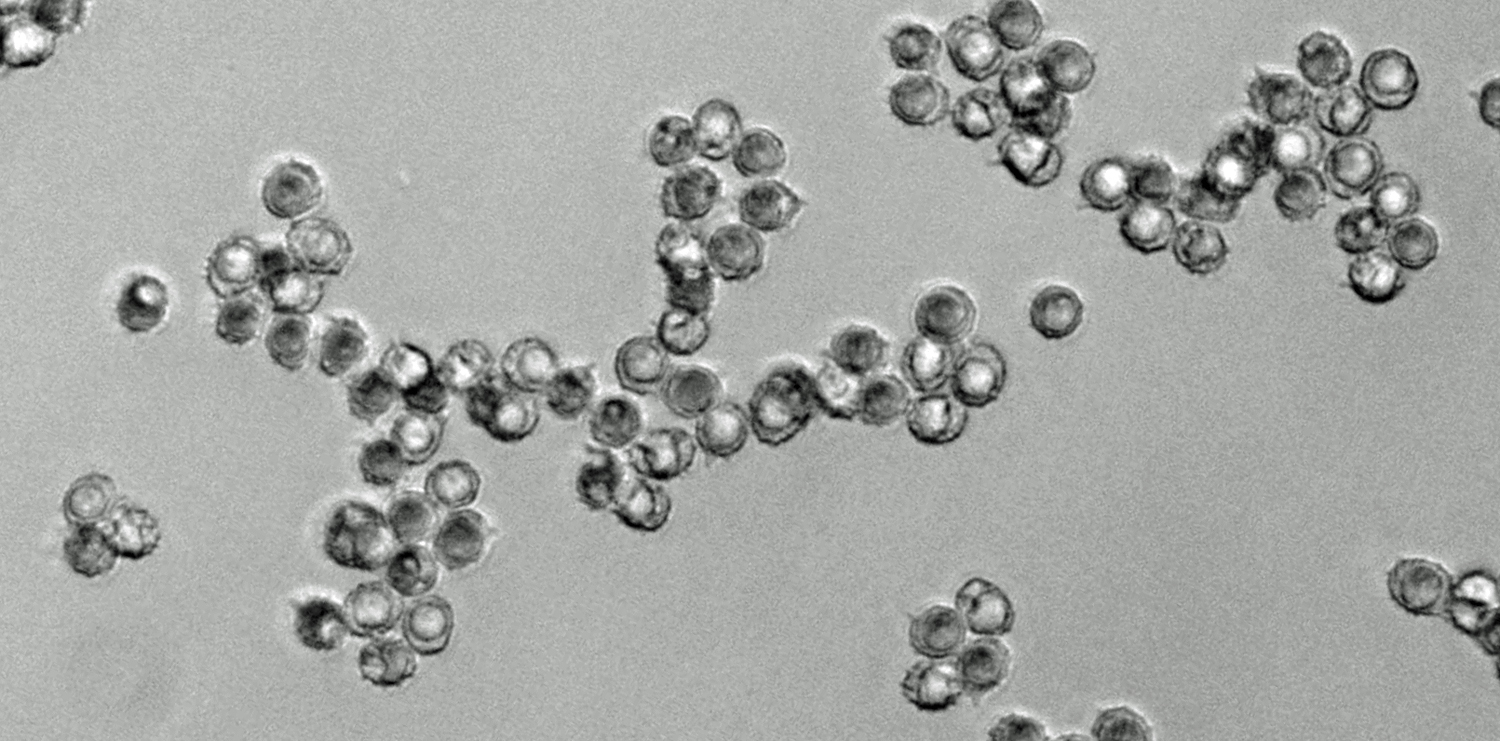

Lactarius chrysorrheus (sometimes spelt Lactarius chrysorheus) is a member of the genus Lactarius, whose many members are commonly known as milkcaps. It has recently been given the English (common) name of the yellowdrop milkcap. It is pale salmon in color, poisonous, and grows in symbiosis with oak trees.

Taxonomy

[edit]First described by the Swedish father of modern mycology Elias Magnus Fries. The specific epithet is derived from the Ancient Greek words chryso- "golden", and rheos "stream".[1] Common names include yellow milkcap,[2] and yellowdrop milkcap.[3]

Description

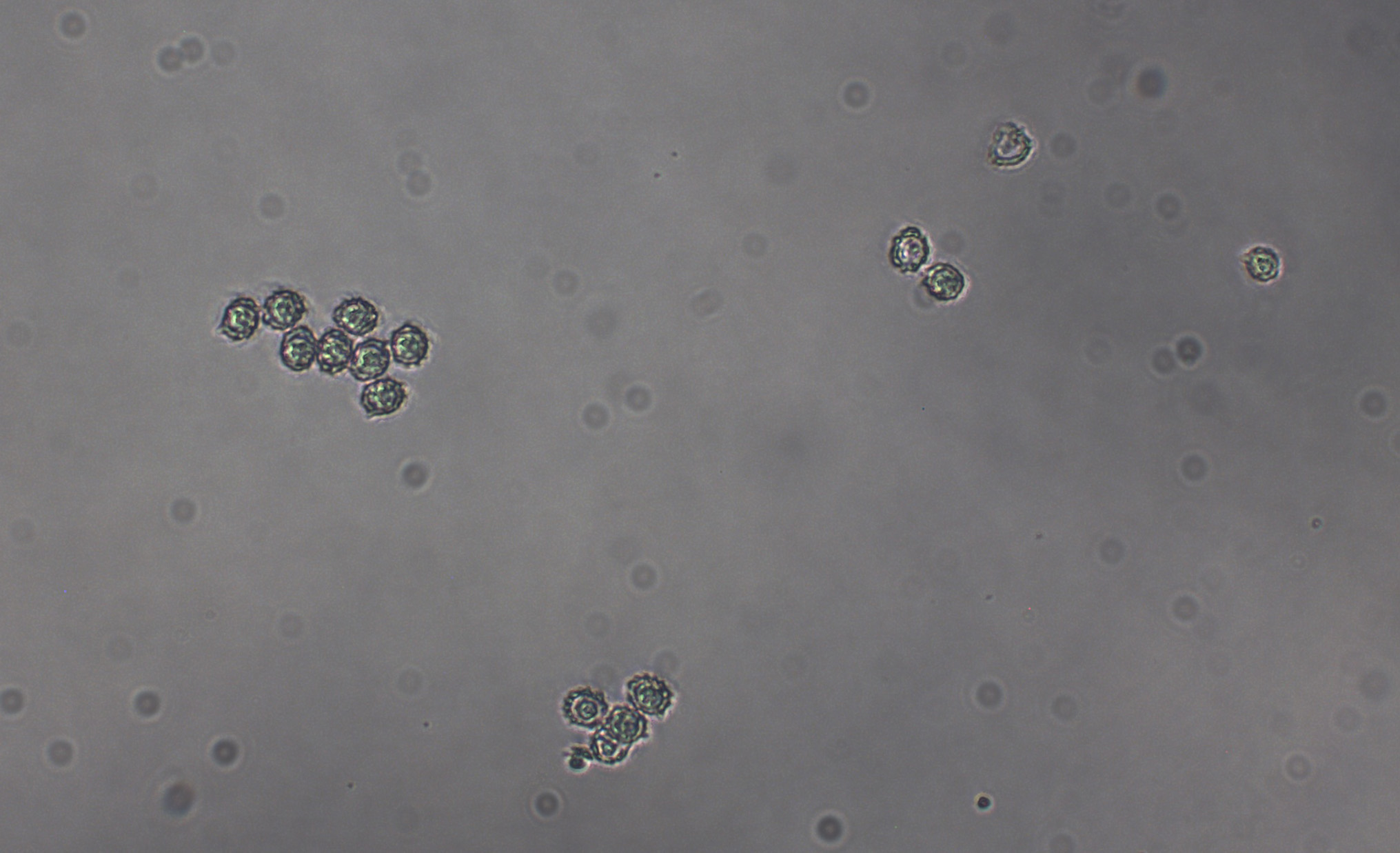

[edit]The cap is 3–8 cm (1.2–3.1 in) in diameter. It is pale salmon, or rosy, with darker markings arranged in rough rings, or bands. At first it is convex, but later flattens, and eventually has a small central depression. It is often somewhat lobed at the edge, and is smooth, with a hairless margin. The whitish to pale buff stipe sometimes has a pink flush on the lower half. It is hollow, cylindrical, or with a slightly swollen base. The gills are decurrent, crowded, and have a pinkish buff tinge, giving a spore print that is creamy white, with a slight salmon tinge. They are quite closely spaced initially. The flesh is white and tastes hot, but is coloured by the copious amounts of milk exuded. This milk is initially white, but when exposed to the air turns bright sulphur yellow in five to fifteen seconds.[3]

Many Lactarius species are similarly coloured, but not too many exude white milk that turns sulphur yellow. However, those that do include Lactarius maculatipes, and Lactarius croceus which are found with hardwoods in the north eastern United States, and Lactarius vinaceorufescens is locally abundant with both hard and soft woods there too.[4] None of these can be found in Britain; Lactarius decipiens is on the British checklist, but is smaller than L. chrysorrheus, and grows with Hornbeam.

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Lactarius chrysorrheus appears in summer and autumn. It is frequent in the northern temperate zones, Europe, North America, and also North Africa. It is mycorrhizal with oak trees in Britain.[5]

Toxicity

[edit]This mushroom contains toxins, and is considered poisonous[2][3] (although it has sometimes been listed as edible).[6] Consumption of the several species of poisonous milkcaps results in predominantly acute gastrointestinal symptoms, which can be severe.[7]

The milk is extremely acrid.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ a b c Lamaison, Jean-Louis; Polese, Jean-Marie (2005). The Great Encyclopedia of Mushrooms. Könemann. p. 49. ISBN 3-8331-1239-5.

- ^ a b c Roger Phillips (2006). Mushrooms. Pan MacMillan. p. 25. ISBN 0-330-44237-6.

- ^ David Arora (1986). Mushrooms Demystified. Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- ^ Thomas Laessoe (1998). Mushrooms (flexi bound). Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7513-1070-0.

- ^ Marcel Bon (1987). The Mushrooms and Toadstools of Britain and North Western Europe. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-39935-X.

- ^ Benjamin, Denis R. (1995). Mushrooms: poisons and panaceas — a handbook for naturalists, mycologists and physicians. New York: WH Freeman and Company. pp. 364–65. ISBN 0-7167-2600-9.