Map Snapshot

51 Records

Status

Found solitary, scattered or in groups on wet ground in mixed forests.

Description

Cap: Small, reddish-brown fading to dull pink in age; convex with umbo (slightly depressed in age); smooth. Latex white or watery-white (does not stain). Usually aromatic likened to odor of maple sugar. Gills: Whitish/pale pink, decurrent, close. Stalk: Colored like cap, smooth or with white hairs at base (J. Solem, pers. comm.).

Latex becomes whey-like and is not staining. Its fragrant odor (compared to maple sugar) becomes more conspicuous upon drying. (L. Biechele, pers. comm.)

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Candy caps | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lactarius camphoratus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Russulales |

| Family: | Russulaceae |

| Genus: | Lactarius |

| Species | |

|

L. camphoratus | |

Candy cap or curry milkcap is the English-language common name for two closely related edible species of Lactarius; Lactarius camphoratus, and Lactarius rubidus. These mushrooms are valued for their highly aromatic qualities and are used culinarily as a flavoring rather than as a constituent of a full meal.

Description and classification

[edit]Candy caps are small to medium-size mushrooms, with a pileus ranging from 2–5 cm in diameter[1] (though L. rubidus and L. rufulus can be slightly larger), and with coloration ranging through various burnt orange to burnt orange-red to orange-brown shades. The pileus shape ranges from broadly convex in young specimens to plane to slightly depressed in older ones; lamellae are attached to subdecurrent. The entire fruiting body is quite fragile and brittle. Like all members of Lactarius, the fruiting body exudes a latex when broken, which in these species is whitish and watery in appearance, and is often compared to whey or nonfat milk. The latex may have little flavor or may be slightly sweet, but should never taste bitter or acrid. These species are particularly distinguishable by their scent, which has been variously compared to maple syrup, camphor, curry, fenugreek, burnt sugar, Malt-O-Meal, or Maggi-Würze. This scent may be quite faint in fresh specimens, but typically becomes quite strong when the fruiting body is dried.

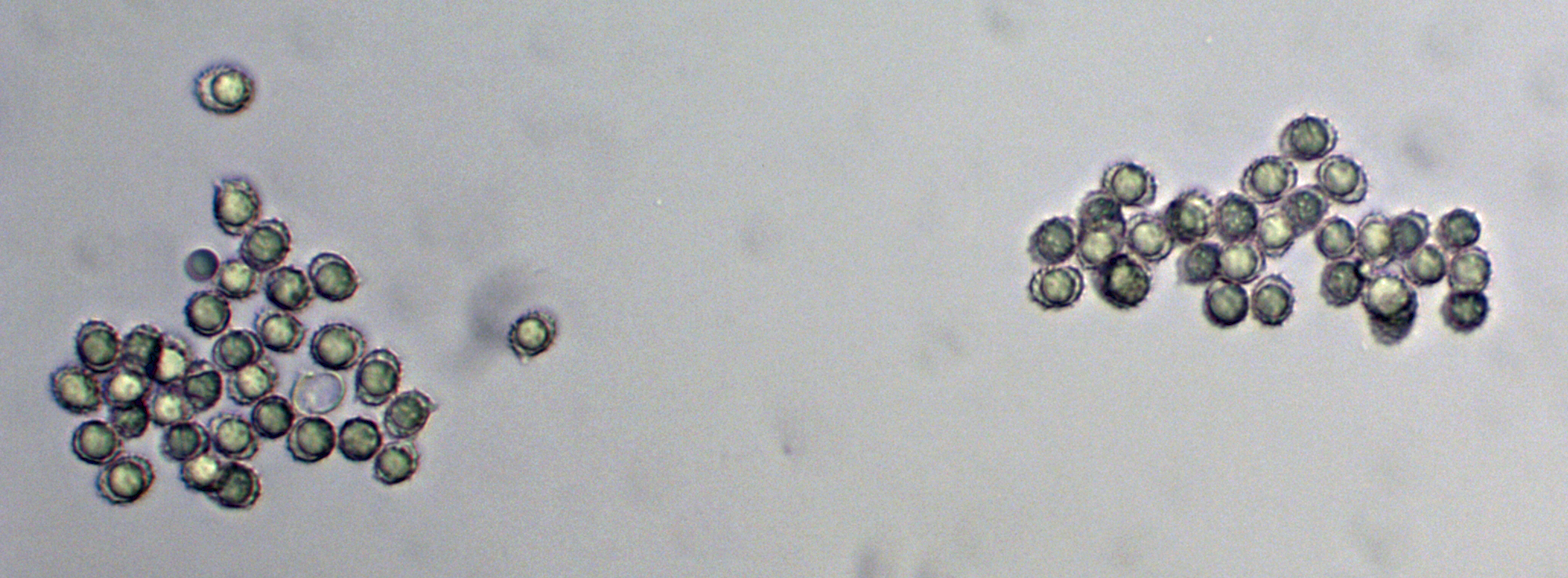

Microscopically, they share features typical of Lactarius, including round to slightly ovular spores with distinct amyloid ornamentation and sphaerocysts that are abundant in the pileus and stipe trama, but infrequent in the lamellar trama.[2]

The candy caps have been placed in various infrageneric groups of Lactarius depending on the author. Bon[3] defined the candy caps and allies as making up the subsection Camphoratini of the section Olentes. Subsection Camphoratini is defined by their similarity in color, odor (with the exception of L. rostratus – see below), and by the presence of macrocystidia on their hymenium. (The other subsection of Olentes, Serifluini, is also aromatic, but have very different aromas from the Camphoratini and are entirely lacking in cystidia.)[4]

Bon[3] and later European authors treated all species that were aromatic and had at least a partially epithelial pileipellis as section Olentes, whereas Hesler and Smith[5] and later North American authors[6] treat all species with such a pileipellis (both aromatic and non-aromatic) as the section Thojogali. However, a thorough molecular phylogenetic investigation of Lactarius has yet to be published, and older classification systems of Lactarius are generally not regarded as natural.[4]

Like other species of Lactarius, candy caps are generally thought to be ectotrophic, with L. camphoratus having been identified in ectomycorrhizal root tips. However, unusually for a mycorrhizal species, L. rubidus is also commonly observed growing directly on decaying conifer wood.[6] All candy cap species seem to be associated with a range of tree species.

| Attribute | L. camphoratus | L. rubidus |

|---|---|---|

| Image |  |

|

| Pileus shape | Papilla sometimes present at disc | Papilla or umbo typically not present |

| Colour | Darker reddish-brown | More deep reddish-brown ("ferruginous") |

| Lamellae | More light yellowish to light orange | More light reddish |

| Spores | Ellipsoid to subglobose; 7.0–8.5 × 6.0–7.5 μm; ornamentation not connected (spines to short ridges) | Subglobose to globose; 6.0–8.5 × 6.0–8.0 μm; ornamentation semi-connected (broken to partial reticulum) |

| Odour | More curry-like | More maple-like; strong only upon drying |

| Distribution | Europe, Asia, eastern North America | Western North America; also reported from Costa Rica[7] |

Identification

[edit]| 'Candy cap' | |

|---|---|

| Gills on hymenium | |

| Cap is convex or flat | |

| Hymenium is decurrent | |

| Stipe is bare | |

| Spore print is white to yellow | |

| Ecology is mycorrhizal | |

| Edibility is choice | |

It is possible to mistake other distasteful or toxic species of mushrooms for candy caps or mistakenly include such species in a larger collection of candy caps. Those inexperienced with mushroom identification may mistake any number of "little brown mushrooms" ("LBMs") for candy caps, including the deadly galerina (Galerina marginata and allies), which can occur in the same habitat. Candy caps can be distinguished from non-Lactarius species by their brittle stipe, while most other "LBMs" have a more flexible stipe. It is therefore recommended that candy caps be gathered by hand, breaking the fragile stipe in one's fingers. By this method, LBM's with a cartilaginous stipe will easily be distinguished.[8]

Candy caps may also be confused with any of a large number of small, similarly colored species of Lactarius that may be distasteful to downright toxic depending on the species and the number consumed.

Candy caps may be distinguished from other Lactarius by the following characteristics[citation needed]:

- Odor: Candy caps have a distinctive odor (described above) that should not be present in other species of Lactarius. However, that other species of Lactarius may have different, but also distinctive, odors. Fresh candy caps (especially Lactarius rubidus) may also not have a noticeable odor, limiting the utility of this characteristic. A sweet odor is much more evident after briefly singeing the flesh of a candy cap with a match or lighter, which can be useful for identification.[9]

- Taste: The flesh and latex of candy caps should always be mild-tasting to somewhat sweet, lacking any hint of bitterness or acridity. Note, however, that there are some species of Lactarius, such as L. luculentus, where the bitterness is subtle and also may not be noticeable for a minute or so after tasting.

- Latex: The latex of candy caps appears thin and whey-like, like milk that has been mixed with water. This latex does not change color nor does it discolor the flesh of the mushroom. Other species of Lactarius have a distinctly white or colored latex, which in some species discolors the flesh of the mushroom.

- Pileus: Candy caps never have a zonate pattern of coloration on the surface of the pileus, nor is the pileus ever even slightly viscid.

Chemistry

[edit]The chemical responsible for the distinct odor of the candy cap was isolated in 2012 by chemical ecologist and natural product chemist William Wood of Humboldt State University, from collections of Lactarius rubidus. The odoriferous compound found in the fresh tissue and latex of the mushroom was found to be quabalactone III, an aromatic lactone. When the tissue and latex is dried, quabalactone III is hydrolyzed into sotolon, an even more powerfully aromatic compound, and one of the main compounds responsible for the aroma of maple syrup, as well as that of curry.[10]

The question of what compound was responsible for the odor of candy cap had been under investigation by Wood and various students for a period of 27 years, when a mycology student in a class he was teaching asked what compound was responsible for the mushroom's odor, triggering investigation into the question. Isolation of the compound remained elusive, until solid-phase microextraction was used to extract the volatile compounds, which were then analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.[10][11]

Earlier investigation of the aromatic compounds of L. helvus by Rapor, et al. had also yielded sotolon (among a large number of other aromatic compounds), which was identified as giving this species its distinct fenugreek odor. Other important volatile compounds identified included decanoic acid and 2-methylbutyric acid.[12]

Analysis of Lactarius camphoratus has shown that it contains 12-hydroxycaryophyllene-4,5-oxide, a caryophyllene compound. However, this was not identified as an aromatic component of this mushroom.[13]

Culinary use

[edit]Candy caps are not typically consumed as a vegetable the way most other edible mushrooms are consumed. Because of the strongly aromatic quality of these mushrooms, they are instead used primarily as a flavoring, much the way vanilla, saffron, or truffles are used. They impart a flavor and aroma to foods that has been compared to maple syrup or curry,[14] but with a much stronger aroma than either of these seasonings. Candy caps are unique among edible mushrooms in that they are often used in sweet and dessert foods, such as cookies and ice cream.[15] They are also sometimes used to flavor savory dishes that are traditionally prepared with sweet accompaniments, such as pork, and are also sometimes used in place of curry seasoning.

They are usually used in dried form, as the characteristic aroma intensifies greatly upon drying. To use them as a flavoring, the dried mushrooms are either powdered or they are infused into one of the liquid ingredients used in the dish, for example, being steeped in hot milk, much the same way whole vanilla beans are.

As a result of these culinary properties, candy caps are highly sought after by many chefs. Lactarius rubidus is commercially gathered and sold in California[15][16] while L. camphoratus is gathered and sold in the United Kingdom [17] and Yunnan Province, China.[18]

Marchand reports that some individuals use L. camphoratus as part of a pipe tobacco mix.[19]

Similar species

[edit]A number of species of Lactarius are distinctly aromatic, though only some of these species are thought to be closely related to the candy cap group.

The subsection Camphoratini includes Lactarius rostratus, a species found in northern Europe, though quite rare.[4] Unlike other members of subsection Camphoratini, L. rostratus has an unpleasant (even nauseating) smell, described as resembling ivy. Lactarius cremor is a name sometimes used for mushrooms in this group, however, Heilmann-Clausen, et al.[4] consider this name to be nomen dubium, referring variously to Lactarius rostratus, L. serifluus, or L. fulvissimus depending on the author's concept of L. cremor. Lactarius mukteswaricus and L. verbekenae, two species described from the Kumaon area of the Indian Himalaya in 2004, are reported to be very closely related to L. camphoratus, including in odor.[20]

Lactarius rufulus is reported by one source as being a "candy cap" species and having a similar odor to the other candy caps,[8] though earlier monographs do not report such an aroma and describe the flavor as subacrid.

Lactarius helvus and L. aquifluus, found in Europe and North America, respectively, are also strongly aromatic and similar to candy caps, the former having the odor of fenugreek. Lactarius helvus is known to be mildly toxic, causing gastrointestinal upset. The edibility of L. aquifluus is unknown, but as it is a close relative of L. helvus, it is suspected of being toxic.[21] Lactarius species with yellow latex (or white latex that turns yellow) may be dangerous.[22]

Lactarius glyciosmus and L. cocosiolens both have a distinct coconut odor.[6][23] L. glyciosmus, however, has a subacrid flavor, though it is reported as having been gathered commercially in Scotland.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Davis, R. Michael; Sommer, Robert; Menge, John A. (2012). Field Guide to Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-520-95360-4. OCLC 797915861.

- ^ Largent DL, Baroni TJ. 1988. How to Identify Mushrooms to Genus VI: Modern Genera. Arcata, CA: Mad River Press. ISBN 0-916422-76-3. p 73–74.

- ^ a b Bon M. 1983. Notes sur la systématique du genre Lactarius. Documents Mycologiques 13(50): 15–26.

- ^ a b c d Heilmann-Clausen J, Verbeken A, Vesterholt J. 1998. The Genus Lactarius. (Fungi of Northern Europe, Volume 2.) Mundelstrup, DK: Danish Mycological Society. ISBN 87-983581-4-6.

- ^ a b Hesler LR, Smith AH. 1979. North American Species of Lactarius. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08440-2.

- ^ a b c Methven AS. 1997. The Agaricales of California 10. Russulales II: Lactarius. Eureka, CA: Mad River Press. ISBN 0-916422-85-2.

- ^ Mueller GM, Halling RE, Carranza J, Mata M, Schmit JP. 2006. Saprotrophic and ectomycorrhizal macrofungi of Costa Rican oak forests. In: M. Kappelle (ed). Ecology and conservation of neotropical montane oak forests. (Ecological Studies Series, Vol. 185). Berlin: Springer Verlag. p 55–68 (p 62). doi:10.1007/3-540-28909-7_5 ISBN 978-3-540-28908-1.

- ^ a b Campbell D. 2004. The candy cap complex. Archived 2006-11-16 at the Wayback Machine Mycena News 55(3):3–4. (scroll down)

- ^ Winkler, Daniel. 2023. Fruits of the Forest: A Field Guide to Pacific Northwest Edible Mushrooms. Seattle, Washington: Skipstone.

- ^ a b Wood WF, Brandes JA, Foy BD, Morgan CG, Mann TD, DeShazer DA. 2012. The maple syrup odour of the "candy cap" mushroom, Lactarius fragilis var. rubidus. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 43:51-53. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2012.02.027.

- ^ Humboldt State University. 2012. Student question about mushroom's maple syrup odor takes 27 years to answer. Humboldt State Now (website). May 04, 2012.

- ^ Rapior S, Fons F, Bessiere J-M. 2000. The fenugreek odor of Lactarius helvus. Mycologia 92(2): 305–308. doi:10.2307/3761565.

- ^ Daniewski WM, Grieco PA, Huffman JC, Rymkiewicz A, Wawrzun, A. 1981. Isolation of 12-hydroxycaryophyllene-4,5-oxide, a sesquiterpene from Lactarius camphoratus. Phytochemistry. 20(12):2733–4. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(81)85276-4.

- ^ Phillips, Roger (2010) [2005]. Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-55407-651-2.

- ^ a b Treviño L. 2004 Jan 9. "Candy Caps let people flavor foods — with fungus: Mushrooms are in cookies and ice cream". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Jung C. 2004 Jan 28. "The rare fungus that can satisfy your sweet tooth". San Jose Mercury. (Archived at Wayback Machine),

- ^ Kirby T. 2006 Sep 27. "The British fascination with fungi: The magic of the curry mushroom" Archived 2007-03-24 at the Wayback Machine. The Independent.

- ^ Wang X-H. 2000. (A taxonomic study on some commercial species in the genus Lactarius (Agaricales) From Yunnan Province, China.[permanent dead link]) Acta Botanica Yunnanica 22(4):419–427. (Article in Chinese. English abstract Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Marchand A. 1980. Champignons du Nord et du Midi 6: Lactaires et Pholiotes. Perpignan, FR: Diffusion Hachette. ISBN 2-903940-03-7.

- ^ Das K, Sharma, JR, Montoya L. 2004. Lactarius (Russulaceae) in Kumaon Himalaya 1: New species of subgenus Russularia. Fungal Diversity 16:23–33. (Abstract.)

- ^ Phillips R. 2006. Lactarius aquifluus. Archived 2006-10-22 at the Wayback Machine Roger's Mushrooms (website). Accessed 2008 Feb 11.

- ^ Davis, R. Michael; Sommer, Robert; Menge, John A. (2012). Field Guide to Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-520-95360-4. OCLC 797915861.

- ^ Russulales News Team. 2007. Lactarius glyciosmus. Archived 2008-02-02 at the Wayback Machine Russulales News (website). Accessed 2008 Feb 11.

- ^ Milliken W, Bridgewater S. nd. Scottish plant uses: Lactarius glyciosmus. Flora Celtica online database, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. Accessed 2008 Feb 11.

- Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified (2nd ed). Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 0-89815-169-4

External links

[edit]- From North American species of Lactarius by L. R. Hesler and Alexander H. Smith, 1979:

- From MushroomExpert.Com by Michael Kuo:

- "Lactarius rubidus", February 2004.

- "Lactarius camphoratus", March 2005.

- "California Fungi: Lactarius rubidus" by Michael Wood & Fred Stevens, MykoWeb.com, 2001

- "Fungus of the Month for October 2005: Lactarius rubidus, candy caps" by Tom Volk.

- "Why we're wild about the curry mushroom" Archived 2013-05-05 at archive.today by Martyn McLaughlin, The Herald, September 28, 2006.

- "Bay Area Mushrooms: Lactarius rubidus and Lactarius rufulus: The Candy Cap" by Debbie Viess, BayAreaMushrooms.org, 2007