Map Snapshot

82 Records

Status

Found solitary or in clusters on ground in forests.

Relationships

Fruiting body: Some shade of yellow, usually unbranched, cylindrical to somewhat flattened; round or pointed tips; usually 1 - 3 inches. (J. Solem, pers. comm.)

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Clavulinopsis fusiformis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clavulinopsis fusiformis in grassland, Shetland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Clavariaceae |

| Genus: | Clavulinopsis |

| Species: | C. fusiformis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Clavulinopsis fusiformis | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Clavulinopsis fusiformis is a clavarioid fungus in the family Clavariaceae. In the UK, it has been given the recommended English name of golden spindles. In North America it has also been called spindle-shaped yellow coral[1] or golden fairy spindle.[2] Clavulinopsis fusiformis forms cylindrical, bright yellow fruit bodies that grow in dense clusters on the ground in agriculturally unimproved grassland or in woodland litter. It was originally described from England and is part of a species complex as yet unresolved.[3]

Taxonomy and etymology

[edit]The species was first described in 1799 by English botanist and mycologist James Sowerby from collections made in Hampstead Heath in London.[4] It was transferred to Clavulinopsis by English mycologist E.J.H. Corner in 1950.[5] Initial molecular research, based on cladistic analysis of DNA sequences, indicates that C. fusiformis is part of a complex of related species.[3]

The specific epithet fusiformis, derived from Latin, means "spindle-shaped".[6]

Description

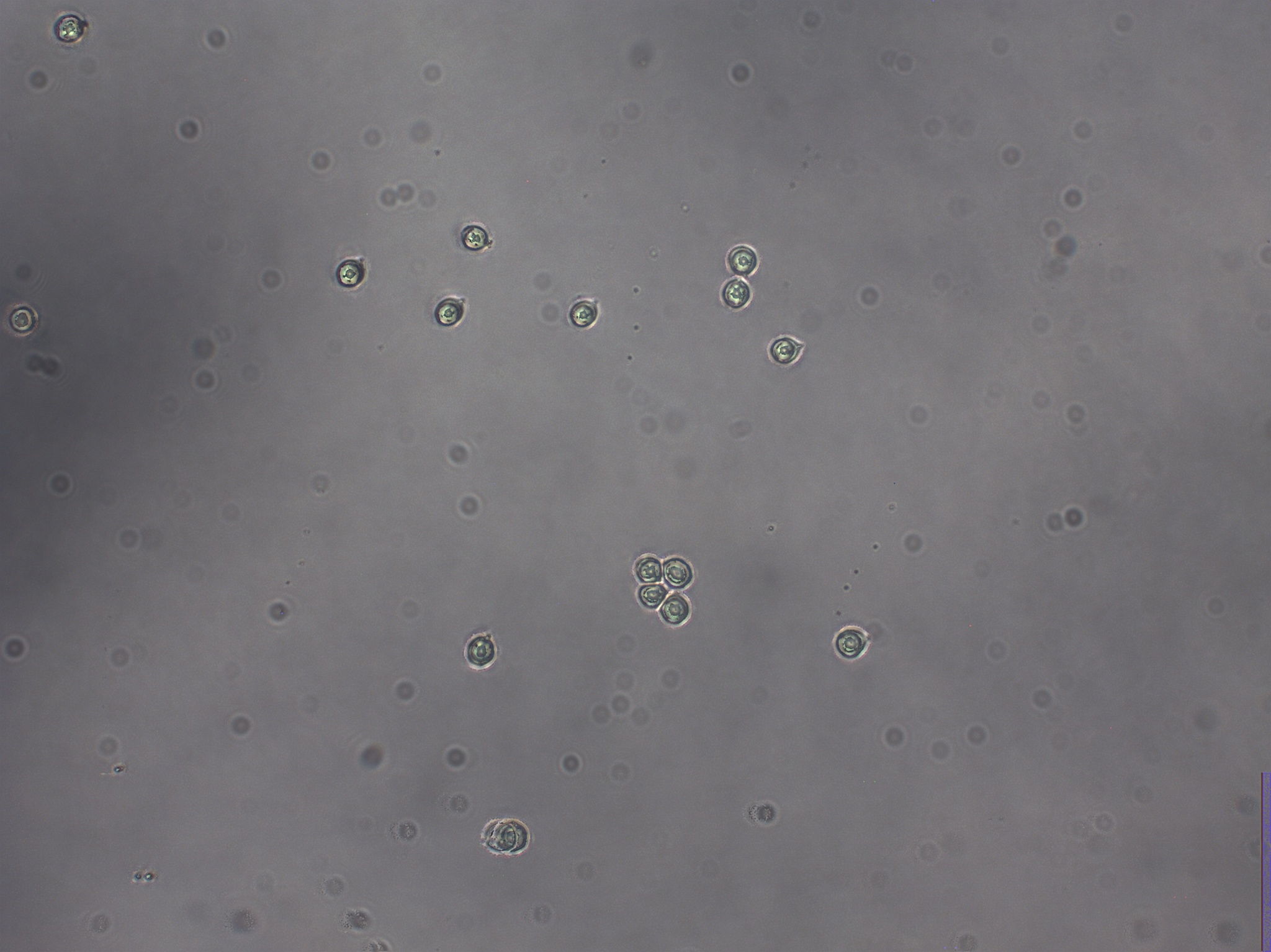

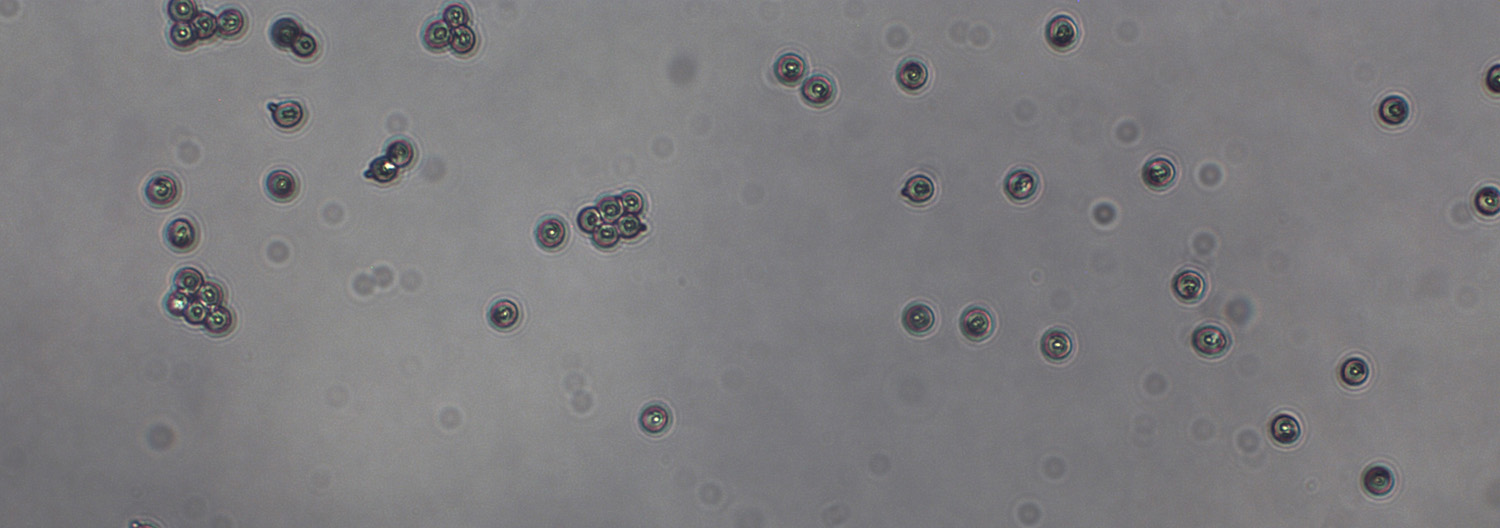

[edit]The fruit bodies of Clavulinopsis fusiformis are cylindrical, bright yellow, up to 150 x 10 mm, growing in fasciculate (densely crowded) clusters. Microscopically, the hyphae are hyaline, up to 12 μm diameter, with clamp connections. The basidiospores are hyaline, smooth, globose to subglobose, 4.5 to 7.5 μm, with a large apiculus.[7]

Similar species

[edit]In European grasslands, Clavulinopsis helvola, C. laeticolor, and C. luteoalba have similarly coloured, simple fruit bodies but are typically smaller and grow singly or sparsely clustered. The uncommon Clavaria amoenoides produces densely clustered fruit bodies but they are pale yellow and, microscopically, lack clamp connections.[8]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

The species was initially described from England and is common throughout Europe. Its distribution outside Europe is uncertain because of confusion with similar, closely related species in the complex.[3] Clavulinopsis fusiformis sensu lato has been reported from North America,[7] Central and South America,[9] and Asia, including Iran,[10] China,[11] Nepal,[12] and Japan.[13]

The species typically occurs in large, dense clusters on the ground and is presumed to be saprotrophic.[14] In Europe it generally occurs in agriculturally unimproved, short-sward grassland (pastures and lawns). Such waxcap grasslands are a declining and threatened habitat, but Clavulinopsis fusiformis is one of the commoner species and is not currently considered of conservation concern. Elsewhere, C. fusiformis sensu lato occurs in woodland. In China it is one of the dominant macrofungal species found in Fargesia spathacea-dominated community forest at an elevation of 2,600–3,500 m (8,500–11,500 ft).[11]

Economic usage

[edit]Fruit bodies are commonly collected and consumed in Nepal,[12][15] where the fungus is known locally as Kesari chyau.[16]

Chemistry

[edit]Extracts of "Clavulinopsis fusiformis" from Japan have been found to contain anti-B red blood cell agglutinin.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Bessette A, Bessette AR, Fischer DW (1997). Mushrooms of Northeastern North America. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-0815603887.

- ^ Russell, Bill (2017-08-01). Field Guide to Wild Mushrooms of Pennsylvania and the Mid-Atlantic: Revised and Expanded Edition. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-08028-4.

- ^ a b c Birkebak JM. "Clavariaceae.org". Retrieved 2023-11-20.

- ^ Sowerby J. (1799). Coloured Figures of English Fungi. Vol. 2. London, UK: J. Davis. p. 98; plate 234.

- ^ Corner EJH. (1950). A monograph of Clavaria and allied genera. Annals of Botany Memoirs. Vol. 1. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 623–4.

- ^ Konstantinidis G. (2005). Elsevier's Dictionary of Medicine and Biology: In English, Greek, German, Italian and Latin. Elsevier. p. 607. ISBN 978-0-08-046012-3.

- ^ a b Petersen RH (1968). "The genus Clavulinopsis in North America". Mycologia Memoir (2): 1–39.

- ^ Roberts P. (2008). "Yellow Clavaria species in the British Isles". Field Mycology. 9 (4): 142–145. doi:10.1016/S1468-1641(10)60593-2.

- ^ Corner EJH (1970). Supplement to 'A monograph of Clavaria and allied genera'. Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia. Vol. 33. Lehre, Germany: J. Cramer. p. 10.

- ^ Saber M. (1989). "New records of Aphyllophorales and Gasteromycetes for Iran". Iranian Journal of Plant Pathology. 25 (1–4): 21–26. ISSN 0006-2774.

- ^ a b Zhang Y, Zhou DQ, Zhao I, Zhou TX, Hyde KD (2010). "Diversity and ecological distribution of macrofungi in the Laojun Mountain region, southwestern China". Biodiversity and Conservation. 19 (12): 3545–3563. doi:10.1007/s10531-010-9915-9. S2CID 24882278.

- ^ a b Christensen M, Bhattarai S, Devkota S, Larsen HO (2008). "Collection and use of wild edible fungi in Nepal". Economic Botany. 62 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1007/s12231-007-9000-9. S2CID 6985365.

- ^ a b Furukuwa K, Ying R, Nakajima T, Matsuki T (1995). "Hemagglutinins in fungus extracts and their blood group specificity". Experimental and Clinical Immunogenetics. 12 (4): 223–231. PMID 8919354.

- ^ Roberts P, Evans S (2011). The Book of Fungi. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0226721170.

- ^ Boa ER. (2004). Wild Edible Fungi: A Global Overview of Their Use and Importance to People. Food & Agriculture Organization. p. 138. ISBN 978-92-5-105157-3.

- ^ Adhikari MK, Devokta S, Tiwari RD (2005). "Ethnomycological knowledge on uses of wild mushrooms in western and central Nepal" (PDF). Our Nature. 3: 13–19. doi:10.3126/on.v3i1.329.