Map Snapshot

19 Records

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Baorangia bicolor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Boletales |

| Family: | Boletaceae |

| Genus: | Baorangia |

| Species: | B. bicolor

|

| Binomial name | |

| Baorangia bicolor (Peck) G.Wu & Zhu L.Yang (2015)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| Baorangia bicolor | |

|---|---|

| Pores on hymenium | |

| Cap is convex | |

| Hymenium is adnate | |

| Stipe is bare | |

| Spore print is olive | |

| Ecology is mycorrhizal | |

| Edibility is edible but not recommended | |

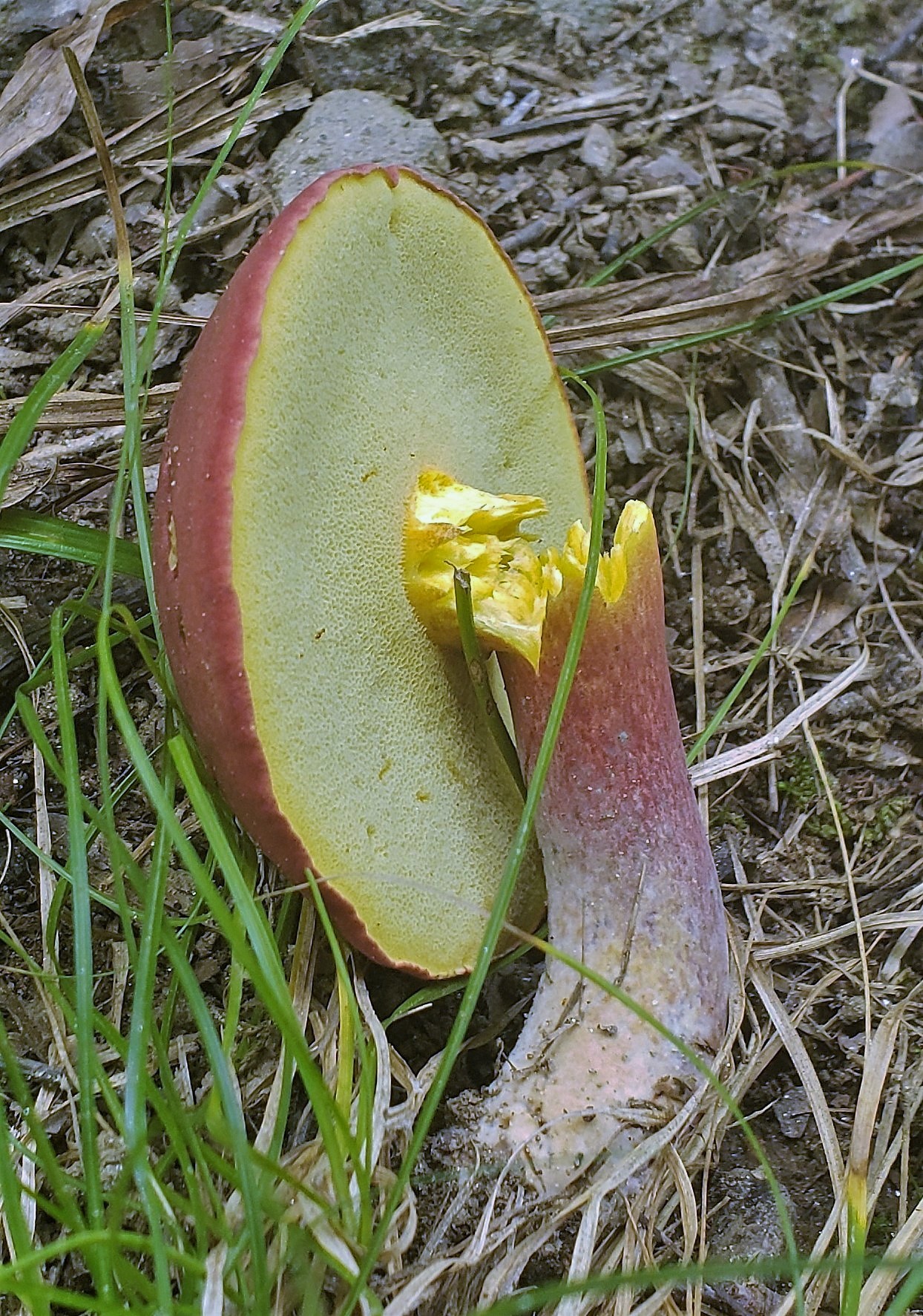

Baorangia bicolor, also known as the two-colored bolete or red and yellow bolete after its two-tone coloring scheme, is an edible fungus in the genus Baorangia. It inhabits most of eastern North America, primarily east of the Rocky Mountains, and is in season during the summer and fall months, but can also be found in China and Nepal. Its fruit body, the mushroom, is classed as medium or large in size, which helps distinguish it from the many similar appearing species that have a smaller stature. A deep blue/indigo bruising of the pore surface and a less dramatic bruising coloration change in the stem over a period of several minutes are identifying characteristics that distinguish it from the similar poisonous species Boletus sensibilis. There are two variations of this species, variety borealis and variety subreticulatus, and several other similar species of fungi are not poisonous.

Taxonomy and naming

[edit]Baorangia bicolor was originally named in 1807 by the Italian botanist Giuseppe Raddi.[2] American mycologist Charles Horton Peck named a species collected in Sandlake, New York, in 1870, Boletus bicolor. Although this naming is considered illegitimate due to article 53.1 of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature,[3] Peck is still given as the authority in the Bessette et al. (2000) monograph of North American boletes.[4] Boletus bicolor (Raddi) is not a synonym of "Boletus bicolor" Peck.[1][5] Peck's Boletus bicolor describes the Eastern North American species that is the familiar "two-colored bolete", while Raddi's Boletus bicolor describes a separate European species that is lost to science.[6] This taxonomic conflict has yet to be resolved. In 1909 a species found in Singapore was named Boletus bicolor by George Edward Massee;[7] this naming is illegitimate and is synonymous with Boletochaete bicolor according to Singer.[8][9] Molecular studies found that Boletus bicolor was not closely related to the type species of Boletus, Boletus edulis, and in 2015 Alfredo Vizzini transferred Boletus bicolor to the genus Baorangia.[10][11][12] The original botanical name for this two-colored bolete was derived from the Latin words bōlētus, meaning "mushroom",[13] and bicolor, meaning "having two colors."[14]

Description

[edit]

The color of the cap of the two-colored bolete varies from light red and almost pink to brick red. The most common coloration is brick red when mature. The cap usually ranges from 5 cm (2.0 in) to 15 cm (5.9 in) in width, with bright yellow pores underneath. The two-colored bolete is one of several types of boletes that have the unusual reaction of the pore surface producing a dark blue/indigo when it is injured, although the reaction is slower than with other bluing boletes. When the flesh is exposed it also turns a dark blue, but less dramatically than the pore surface.[15] Young fruit bodies have bright yellow pore surfaces that slowly turn a dingy yellow in maturity.

The stem of the two-colored bolete ranges from 5 cm (2.0 in) to 10 cm (3.9 in) in length and ranges from 1 cm (0.4 in) to 3 cm (1.2 in) in width. The stem coloration is yellow at the apex and a red or rosy red for the lower two thirds. When injured it bruises blue very slowly and may hardly change color at all in some cases. The stem lacks a ring and lacks a partial veil.[16]

Microscopic characteristics

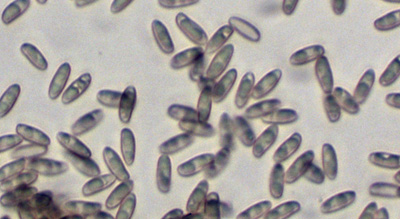

[edit]The spore deposit of the two-colored bolete is olive-brown. Viewed with a microscope, the spores are slightly oblong to ventricose in face view; in profile view, the spores are roughly inequilateral to oblong, and have a shallow suprahilar depression. The spores appear nearly hyaline (translucent) to pale dingy ochraceous when mounted in potassium hydroxide solution (KOH), have a smooth surface, and measure 8–12 by 3.5–5 μm. The tube trama is divergent and gelatinous, originates from a single central strand, not amyloid, and will often stain yellow-brown when placed in dilute potassium hydroxide (KOH).[17]

Chemical tests

[edit]Further methods of identification are chemical tests. With the application of FeSO4 to the cap cuticle (pileipellis), it will turn a dark grey, almost black color and with the application of potassium hydroxide or NH4OH it has a negative coloration. The context stains a bluish grey to an olive green when FeSO4 is applied to it, a pale orange to a pale yellow with the application of KOH, and negative with the application of NH4OH.[16]

Edibility

[edit]The two-colored bolete is an edible mushroom, although some may have an allergic reaction after ingestion that results in stomach upset.[18] The mushroom has a very mild to no taste[19] although it is said to have a very distinctive taste like that of the king bolete[clarification needed]. It can be cooked several ways, and the varying color of the cap can be used to determine if the mushroom is ready to be eaten. If the cap is a lighter red, then it is less mature and is in a stage where it is often larva infested or it can be soft fleshed, in some cases both. The cap should have a dark brick red color when safe to eat.[20][citation needed] Drying the two-colored bolete is a good method for storage. It is important to note the time it takes for the two-colored bolete to bruise when identifying it for consumption; the mushroom should take several minutes to bruise compared to the instant bruising of Boletus sensibilis, which is poisonous and has many of the same visual characteristics of the two-colored bolete.[18]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The two-colored bolete is distributed from southeastern Canada and the Great Lakes Region, primarily east of the Rocky Mountains, as far south as the Florida peninsula, and out to the Midwest as far as Wisconsin. It is commonly found in deciduous woodland and usually grows under or close to broad-leaved trees, especially oak.[15] It can be found in isolation and in groups or clusters, primarily during June through October.[21] The two-colored bolete is also found in China and Nepal, where it is one of the most used mushrooms of over 200 species of edible mushrooms used in Nepal.[22] This unusual distribution of the two-colored bolete and other mushrooms is known as the Grayan disjunction; the phenomenon is characterized by a species living in one continent or island and then also on the other side of the world with no specimens of the species living in between the specific habitats. The Grayan disjunction is not uncommon among fungi.[23]

Similar species

[edit]

The two-colored bolete has several species that are similar to it and the differences are minute in most cases. Boletus sensibilis differs from the two-colored bolete in that it has an immediate bruising reaction and is poisonous, causing stomach upset if ingested, and in some cases a severe allergic reaction.[24][25] B. miniato-olivaceus has a full yellow stem and slightly lighter cap coloration. It also has a more immediate bruising reaction than the two-colored bolete and the stem is slightly longer in proportion to the cap.[26] B. peckii differs from the two-colored bolete by having a smaller average size, a rose red cap that turns almost brown with age, flesh that is paler in color, and a bitter taste. B. speciosus differs from the two-colored bolete by having a fully reticulated stem, more brilliant colors, and very narrow cylindrical spores.[27] Hortiboletus rubellus subsp. rubens and the two-colored bolete have been found to have almost no difference between them, and they cannot be distinguished by appearance alone.[26] Boletus bicoloroide is very similar to the two-colored bolete, the major differences between them being B. bicoloroide has only been found in Michigan and has larger spores. B. bicoloroide is also slightly larger than the two-colored bolete, around 1 cm (0.4 in) longer in the stem and 1 cm (0.4 in) in the cap. This species has not been as thoroughly researched as the two-colored bolete, thus macrochemical tests, edibility, distribution range, and the spore print color are all unknown.[28]

Varieties

[edit]There are two varieties of the two-colored bolete: borealis and subreticulatus.[29] Both varieties have a very similar habitat to that of the main species, except they appear to be limited to just the North American continent. Both varieties also have a slightly different coloration than that of the two-colored bolete, have deeper pores, and are not as often eaten or used in regional recipes.[17]

Variety borealis

[edit]Variety borealis has a slightly darker color scheme than the main species. The coloration in general is darker; the cap can vary from a bright apple red to a dark brick red with maturity, to almost purple in some instances. The pore surface has a varying coloration of orange red to red and becoming a dull brown red with age. The bruising coloration is a blue green and the spore print is olive brown. The distribution of variety borealis is relatively small, ranging from Michigan to the upper New England states. The similar distribution and coloration to Boletus carminiporus has caused the two to be confused.[17] New molecular evidence shows that borealis is not closely related to Baorangia bicolor var. bicolor.[10]

Variety subreticulatus

[edit]Variety subreticulatus, like variety borealis, has a generally darker coloration than the two-colored bolete, but varies much more than either. When fresh the coloration of the cap varies from a rose red, red, rose pink, dark red, and purple red. With age it changes to a cinnamon red or a rusty rose color, with yellowing toward the margin. The pore surface is similar to that of the main species–yellow when fresh and with age changing to a dull ochre yellow; the bruising coloration is blue but is much lighter and sometimes not appearing to stain when bruised at all. The spore print is olive brown.[17] The distribution of variety subreticulatus is very similar to the distribution of the two-colored bolete in North America, and appears north to eastern Canada and south to Florida, and west to Wisconsin.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Boletus bicolor Peck, Annual Report on the New York State Museum of Natural History, 24: 78, 1872". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- ^ (Raddi 1807, pp. 62–345)

- ^ "Boletus bicolor Peck". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ (Bessette, Roody & Bessette 2000, pp. 97–98)

- ^ "Boletus bicolor Raddi, Memorie di Matematica e di Fisica della Società Italiana di Scienze Residente in Modena, 13 (2): 352, t. 5:4, 1807". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ^ Snell, W.H.; Dick, E.A. (1941). "Notes on Boletes. VI". Mycologia. 33 (1): 23–37. doi:10.2307/3754732. JSTOR 3754732. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2013-05-10.

- ^ (Massee 1909, pp. 9–204)

- ^ Singer R. (1986). The Agaricales in Modern Taxonomy (4th ed.). Königstein im Taunus, Germany: Koeltz Scientific Books. p. 796. ISBN 3-87429-254-1.

- ^ "Boletus bicolor Massee 1909". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Nuhn ME, Binder M, Taylor AF, Halling RE, Hibbett DS (2013). "Phylogenetic overview of the Boletineae". Fungal Biology. 117 (7–8): 479–511. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2013.04.008. PMID 23931115.

- ^ Wu G, Feng B, Xu J, Zhu XT, Li YC, Zeng NK, Hosen MI, Yang ZL (2014). "Molecular phylogenetic analyses redefine seven major clades and reveal 22 new generic clades in the fungal family Boletaceae". Fungal Diversity. 69 (1): 93–115. doi:10.1007/s13225-014-0283-8. S2CID 15652037.

- ^ Vizzini A. (2015). "Nomenclatural novelties" (PDF). Index Fungorum (235): 1. ISSN 2049-2375.

- ^ "bōlētus". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "bicolor". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ a b (Wernert 1982)

- ^ a b (Bessette, Roody & Bessette 2000, p. 97)

- ^ a b c d e (Smith & Theirs 1971, p. 275)

- ^ a b Phillips, Roger. "Boletus bicolor". RogersMushrooms. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ "Boletus bicolor". New Jersey Mycological Association. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ Report, Mushroom. "Boletus bicolor". Mushroom Report. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ (Bessette, Roody & Bessette 2000, p. 98)

- ^ (Christensen et al. 2008)

- ^ (Vasilyeva & Stephenson 2010, p. 284)

- ^ Kuo, Michael (2003). "Boletus bicolor". MushroomExpert.Com Web. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Lamoureux, Yves (2009). "Fungus Portraits No.2. Two-colored BoleteBoletus bicolor". Le Cercle des mycologues de Montréal (CMM). Le Mycologue. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ a b (Coker 1974, p. 64)

- ^ (Coker 1974, p. 65)

- ^ (Bessette, Roody & Bessette 2000, p. 99)

- ^ (Smith & Theirs 1971, p. 278)

Bibliography

[edit]- Bessette, Alan; Roody, William; Bessette, Arleen (April 2000). North American Boletes: A Color Guide to the Fleshy Pored Mushrooms (1st ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0588-9.

- Christensen, Morten; Bhattarai, Sanjeeb; Devkota, Shiva; Larsen, Helle (2008). "Collection and Use of Wild Edible Fungi in Nepal". Economic Botany. 62 (1): 12–23. Bibcode:2008EcBot..62...12C. doi:10.1007/s12231-007-9000-9. S2CID 6985365.

- Coker, William; Beers, Alma (1974) [1943]. The Boleti of North Carolina (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20377-8.

- Massee, GE. (1909). "Fungi exotici, IX". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Informations of the Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. 1909 (5): 204–9 (see p. 205). doi:10.2307/4113287. JSTOR 4113287.

- Raddi, G.F. (1807). "Delle specie nuove di Funghi ritrovatanei contorni di Firenze". Atti della Societá dei Naturalisti e Matematici di Modena (in Italian). 13: 345–62.

- Smith, Alexander H.; Theirs, Harry D. (1971). The Boletes of Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library. ISBN 0-472-85590-5.

- Vasilyeva, Larissa; Stephenson, Steven (2010). "Biogeographical patterns in pyrenomycetous fungi and their taxonomy. 1. The Grayan disjunction". Mycotaxon. 114: 281–303. doi:10.5248/114.281.

- Wernert, Susan J. (1982). Reader's Digest North American Wildlife. Pleasantville, NY: Reader's Digest Association. ISBN 0-89577-102-0.

External links

[edit]- YouTube Video:Foraging, Boletus sensibilis and Boletus bicolor by Bill Yule, Connecticut Valley Mycological Society

- article 53.1 of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature