Map Snapshot

9 Records

Status

The species was previously reported as Heterobasidion annosum, which is now thought to be restricted to Europe. Heterobasidion irregulare is the North American counterpart.

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Heterobasidion irregulare | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. irregulare

|

| Binomial name | |

| Heterobasidion irregulare Garbel. & Otrosina (2010)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Polyporus annosus | |

Heterobasidion irregulare is a tree root rotting pathogenic fungus that belongs to the genus Heterobasidion, which includes important pathogens of conifers and other woody plants. It has a wide host and geographic range throughout North America and causes considerable economic damage in pine plantations in the United States. This fungus is also a serious worry in eastern Canada. Heterobasidion irregulare has been introduced to Italy (Lazio)(modifica) where it has been responsible for extensive tree mortality of stone pine.[1] Due to the ecology, disease type, host range/preference, interfertility group, and genetic information, H. irregulare (formerly known as Heterobasidion annosum P ISG) was designated a new species and distinguished from Heterobasidion occidentale (formerly known as Heterobasidion annosum S ISG).[2]

Hosts, Symptoms and Signs

[edit]

Many woody plant species have been reported as hosts for H. irregulare. Hosts consist of pines and some other conifers and hardwoods, including ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa),[3] shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), red pine (Pinus resinosa),[4] incense-cedar (Calocedrus decurrens), western juniper (Juniperus occidentalis), and Manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.).[3]

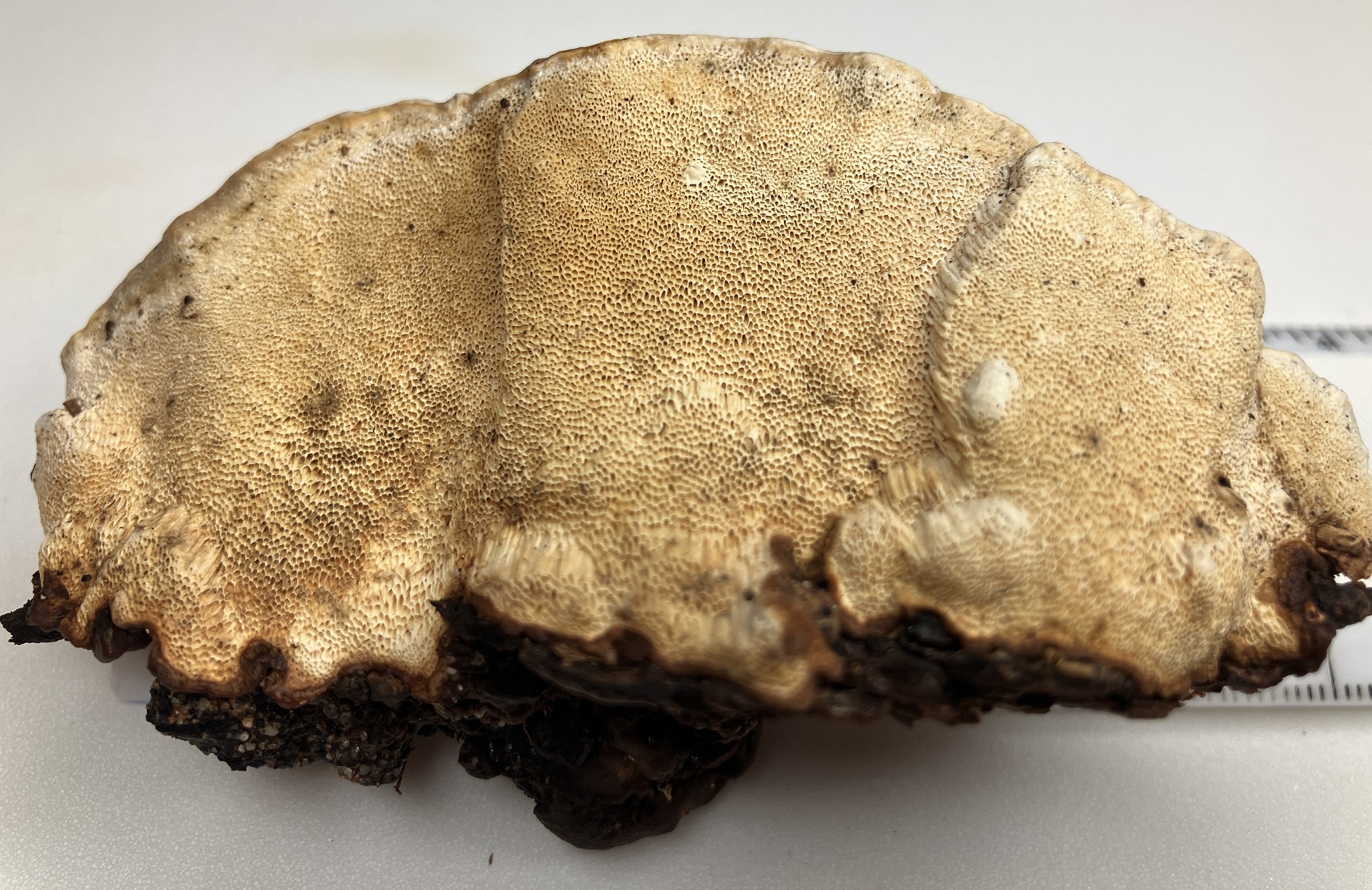

Heterobasidion irregulare causes both above and below-ground symptoms. Above-ground symptoms of infected trees consist of reduced height growth, patches of dead and declining trees, wind-thrown trees, reduced shoot and diameter growth, and resin-soaking at the root collar. Additionally, the crown may become thin and foliage (leaves or needles) becomes chlorotic. The characteristic symptom of most tree root disease, including this type, is a disease center.g This occurs when the fungus has infected one tree and then spreads through the roots to other trees and kills them too. This creates a pattern of old dead trees in the center of the pocket and progressively newer dead, chlorotic, then healthy trees, usually in a circular area. Below-ground symptoms of H. irregulare include excessive pitch production, stringy, white root decay, and root lesions. Signs include the formation of white mycelia between bark scales followed by conks (fruit bodies) that usually form in the duff layer at the base of the tree or stump.[5][6][7] The fruit bodies can also form as "foam" on the ground rising from roots under the surface.[citation needed]

Disease cycle

[edit]The disease cycle of Heterobasidion irregulare begins with natural wounds on trees or cut stumps. Basidiospores are wind-blown and land on tree wounds. Most spores land within 100 metres of the fruiting bodies.[8] The spores then germinate and the mycelia, or vegetative structure of the fungus, grows into the wood. The mycelia colonizes the wood by decomposing the lignin and cellulose, producing a stringy white rot. It spreads from tree to tree by root grafts, killing trees in an ever-widening circle.[9] The sexual reproductive structures of the fungus, annual or perennial basidiocarps, appear on decomposing stumps and at the base of dead trees and release spores in summer and fall to mid-winter.[10] The highest sporulation occurs from late summer to when the conks freeze. When the conk temperatures are above freezing the spores of the fungus are released and carried by wind currents to land in open wounds or stumps of cut trees.[9] The fungus can survive freezing temperatures both as mycelia and as basidiocarps, and overwinters in the roots and stem tissue of trees. The mycelia produce infectious conidia, but it is unknown how these fit into the disease cycle. When the fungus has obtained enough nutrients it grows a basidiocarp on the outside of a trunk or stump of a tree in the eastern US or inside a hollow stump in the western US.[2]

Environment

[edit]Various abiotic factors attribute to the ability of Heterobasidion irregulare to cause disease on trees. Factors such as gaseous regime (oxygen levels), pH of the soil, and moisture content, may affect fungal growth.[11] Disease is most severe on high fertility or lime, alkaline (pH>6), or former agricultural soils. H. irregulare grows best on well drained sandy soils, which are now farm fields that have been converted into plantations in the southern US.[12] Plantations particularly favor this fungus because it enters the plant through a wound or cut surface and then spreads by the roots.[4] Research on temperature requirements for germination and spore production is currently being conducted. It is known however, that H. irregulare is able to germinate at temperatures as low as 8 °C (46 °F).[13]

Management

[edit]The best strategy to manage this disease is to avoid infection of stumps. To do this, do not cut trees at major sporulation times, which are summer to late fall, and treat fresh stumps with protectants such as borax, which is registered as cellu-treat or sporax, either as a powder or in aqueous form. These treatments are most effective if done immediately after stump is created (the tree is cut). Other control measures include: use wide spacing when planting to reduce the need for thinning and reduce the potential root grafts, thin only when spores are less abundant, (January through March), and plant tree species that are less susceptible.[9] Another strategy is to avoid logging injuries as the spores enter through such injuries and infect and kill the tree and begin a disease center. Once the fungus is in the stand there is nothing that can be done about it except extremely expensive stump removal and prevention of new infections.[citation needed]

There are bio-controls used in Europe against the Heterobasidion species found there. However, they are not approved for use in the United States and it is uncertain whether they work on Heterobasidion irregulare because of the recent naming of this species, and not much research has been done outside of the US on its reaction to biocontrols.[citation needed]

Importance

[edit]This disease is economically important because of its effect on timber species, especially in plantations in the Midwest and Southeast in the United States. It destroys commercially viable trees and causes losses both from reduction of marketable wood and increased cost of treatment to growers. It reduces both volume and height growth as well as eventually killing the trees and causing them to be more susceptible to windthrow and other diseases and insects. In the Southeastern US it was found that as many as 30% of trees can be killed in severely infected stands.[4]

Heterobasidion irregulare is also an ecologically important disturbance agent in natural settings. It creates gaps in forest canopies, allowing light and water to get through, which in turn allows a diversity of plants to establish. It also stresses trees, making them more susceptible to different fungi and insects, particularly bark beetles.[14] These stressed trees can then act as a source of infection by other organisms of nearby healthy trees.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ EPPO (October 2013). "Heterobasidion irregulare". European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization. Archived from the original on 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ^ a b Otrosina, W. J., Garbelotto M.2010. Heterobasidion occidentale sp. nov. and Heterobasidion irregulare nom. nov.: A disposition of North American Heterobasidion biological species. Fungal Biology 114 (2010) 16–25

- ^ a b Drummond, D. B; Bretz, T. W. 1967. Seasonal fluctuations of airborne inoculum of Fomes annosus in Missouri. Phytopathology 57: 340.

- ^ a b c Robbins, K.1984. Annosus Root Rot in Eastern Conifers. Forest insect and disease leaflet 76 U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service.

- ^ Cram M. M. 2009. Annosum Root Rot. Heterobasidion annosum. http://www.bugwood.org/factsheets/98-031.html

- ^ Scanlon K. 2011. ANNOSUS ROOT ROT. BIOLOGY, SYMPTOMS AND PREVENTION. U.S. Wisconsin Dept of Natural Resources, Forest Health Protection.

- ^ Schmitt C. L.1989. Diagnosis of Annosus Root Disease in Mixed Conifer Forests in the Northwestern United States. Symposium on Research and Management of Annosus Root Disease in Western North America.

- ^ Gontheir, P; Lione, G; Giodana, L; Garbelotto, M (2012). "The American forest pathogen Heterobasidion irregulare colonizes unexpected habitats after its introduction in Italy". Ecological Applications. 22 (8): 2135–2143. doi:10.1890/12-0420.1. PMID 23387115.

- ^ a b c Filip, G. M. and Morrison, D. J., 1998. "North America" edited by Woodward, S.; Stenlid, J.; Karjalainen, R.; and Huttermann, A.; Heterobasidion annosum Biology, Ecology, Impact and Control. Cab International UK, University Press, Cambridge.

- ^ Korhonen, K. and Stenlid, J. 1998. "Biology of Heterobasidion annosum" edited by Woodward, S.; Stenlid, J.; Karjalainen, R.; and Huttermann, A.; Heterobasidion annosum Biology, Ecology, Impact and Control. Cab International UK, University Press, Cambridge

- ^ Maijala P.2000. Heterobasidion annosum and wood decay: Enzymology of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin degradation. http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/julkaisut/mat/bioti/vk/maijala

- ^ Froelich, R. C.; Dell, T. R.; Walkinshaw, C. H.1966. Soil Factors Associated with Fomes annosus in the Gulf States. Society of American Foresters. 12:3, 356-361.

- ^ Cowling E. B.; Kelman A. 1964. Influence of Temperature Growth of Fomes annosus Isolates.Phytopathology 54: 249-372

- ^ Otrosina, William J. and Cobb, Fields W. Jr. 1989. Biology, Ecology, and Epidemiology of Heterobasidion annosum. Proceedings of the Symposium on Research and Management of Annosus Root Disease (Heterobasidion annosum) in Western North America. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-116