Map Snapshot

12 Records

Description

Cap: Broadly convex, brown, often cracked in maturity; flesh unchanging or slowly changing to red. Pores: Grayish-white, stain brown. Stalk: Whitish stalk with dark scabers; may have blue stains near base; flesh unchanging or upper portion may change to red, may have blue stains near base (J. Solem, pers. comm.).

Where To Find

Habitat: Solitary or groups under birch.

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Leccinum scabrum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Boletales |

| Family: | Boletaceae |

| Genus: | Leccinum |

| Species: | L. scabrum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leccinum scabrum | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Leccinum scabrum | |

|---|---|

| Pores on hymenium | |

| Cap is convex | |

| Hymenium is adnate | |

| Stipe is bare | |

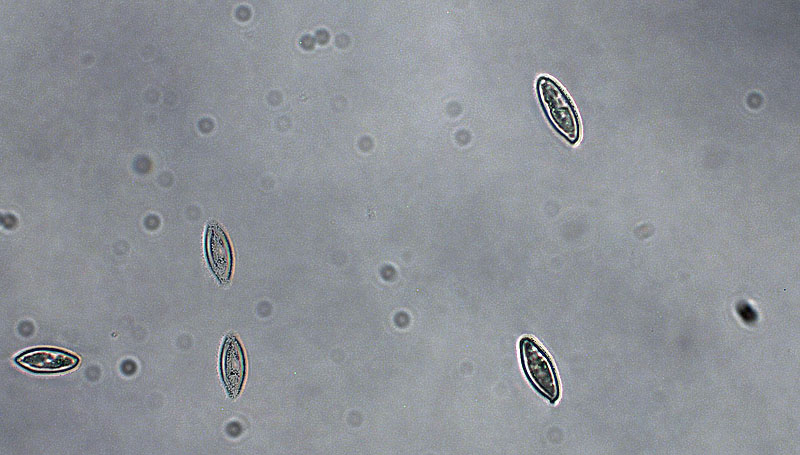

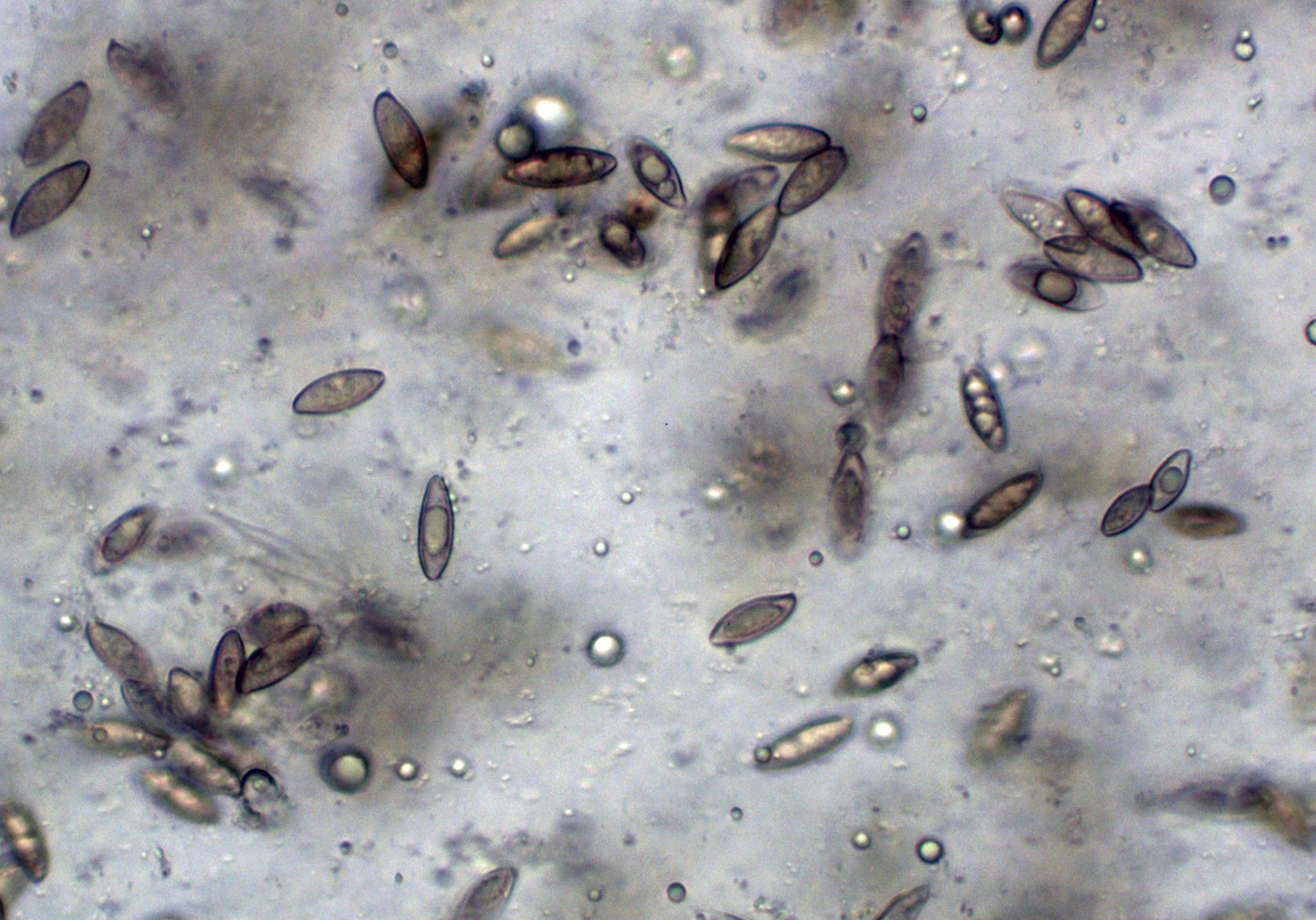

| Spore print is olive | |

| Ecology is mycorrhizal | |

| Edibility is edible | |

Leccinum scabrum, commonly known as the rough-stemmed bolete, scaber stalk, and birch bolete, is an edible mushroom in the family Boletaceae, and was formerly classified as Boletus scaber. The birch bolete is widespread in Europe, in the Himalayas in Asia, and elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere, occurring only in mycorrhizal association with birch trees. It fruits from June to October.[1][2] This mushroom is also becoming increasingly common in Australia and New Zealand where it is likely introduced.

Description

[edit]

The cap is 5–15 cm (2–6 in) wide. At first, it is hemispherical, and later becomes flatter. The skin of the cap is tan or brownish, usually with a lighter edge;[3] it is smooth, bald, and dry to viscid.[3]

The pores are whitish[3] at a young age, later gray. In older specimens, the pores on the pileus can bulge out, while around the stipe they dent in strongly. The pore covering is easy to remove from the skin of the pileus.

The stipe is 5–15 cm (2–6 in) long and 1–3.5 cm (3⁄8–1+3⁄8 in) wide, slim, with white and dark to black flakes, and tapers upward.[3] The basic mycelium is white.

The flesh is whitish, sometimes darkening following exposure.[3] In young specimens, the meat is relatively firm, but it very soon becomes spongy and holds water, especially in rainy weather. When cooked, the meat of the birch bolete turns black.

Leccinum scabrum has been found in association with ornamental birch trees planted outside of its native range, such as in California.[4]

Similar species

[edit]Several different species of Leccinum mushrooms are found in mycorrhiza with birches, and can be confused by amateurs and mycologists alike. L. variicolor has a bluish stipe. L. oxydabile has firmer, pinkish flesh and a different pileus skin structure. L. melaneum is darker in color and has yellowish hues under the skin of the pileus and stipe. L. holopus is paler and whitish in all parts.

Habitat and distribution

[edit]Leccinum scabrum is a European species that has been introduced to various areas of the world, mostly appearing in urban areas.[3] In New Zealand, it associates solely with Betula pendula.[5]

Uses

[edit]The birch bolete is edible but considered not to be worthwhile by some guides.[6] It can be cooked in various mushroom dishes.[7] It can also be pickled in brine or vinegar. It is commonly harvested for food in Finland and Russia.[8]

A few reports in North America (New England and the Rocky Mountains) after 2009 suggest that Leccinums (birch boletes) should only be consumed with much caution.[9][10]

In Nordic countries all Leccinum species are considered likely poisonous unless cooked for at least 15-20 minutes.[11][12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Fergus, C. Leonard & Charles (2003). Common Edible & Poisonous Mushrooms of the Northeast. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-8117-2641-X.

- ^ Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. pp. 541–542. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Trudell, Steve; Ammirati, Joe (2009). Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest. Timber Press Field Guides. Portland, OR: Timber Press. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-88192-935-5.

- ^ "Leccinum scabrum". California Fungi. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ McNabb RFR. (1968). "The Boletaceae of New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 6 (2): 137–76 (see p. 169). doi:10.1080/0028825X.1968.10429056.

- ^ Phillips, Roger (2010). Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-55407-651-2.

- ^ Francis-Baker, Tiffany (2021). Concise Foraging Guide. The Wildlife Trusts. London: Bloomsbury. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4729-8474-6.

- ^ Ohenoja, Esteri; Koistinen, Riitta (1984). "Fruit body production of larger fungi in Finland. 2: Edible fungi in northern Finland 1976–1978". Annales Botanici Fennici. 21 (4): 357–66. JSTOR 23726151.

- ^ Bakaitis, Bill. "Diagnosis at a Distance". Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ Land, Leslie. "Wild Mushroom Warning: The Scaber Stalks (Leccinum species) May No Longer Be Considered Safe". Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "Poisonous mushrooms in Norway". Poisons Information Centre. 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Tegelsopp. Leccinum versipelle". Svampguiden.

Further reading

[edit]- Kallenbach: Die Röhrlinge (Boletaceae), Leipzig, Klinkhardt, (1940–42)

- Gerhardt, Ewald: Pilze. Band 2: Röhrlinge, Porlinge, Bauchpilze, Schlauchpilze und andere, (Spektrum der Natur BLV Intensiv), (1985)

External links

[edit]- (in German) Pilzgalerie: Leccinum scabrum (Birkenpilz)