Map Snapshot

87 Records

Status

Found solitary to overlapping clusters on decaying wood, usually deciduous, sometimes on wounds of living trees.

Description

Hard, thick, concentrically furrowed, shelf-like fruiting body, thickened at attachment; margin often white, thin. White pores stain brown quickly when scratched/etched giving rise to the common name.

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (December 2013) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Artist's bracket | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Polyporales |

| Family: | Ganodermataceae |

| Genus: | Ganoderma |

| Species: | G. applanatum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ganoderma applanatum | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

| Ganoderma applanatum | |

|---|---|

| Pores on hymenium | |

| No distinct cap | |

| Hymenium is decurrent | |

| Lacks a stipe | |

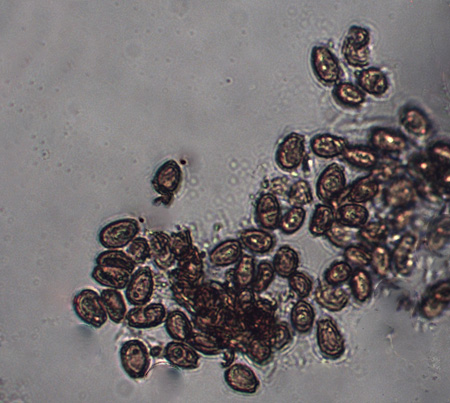

| Spore print is brown | |

| Ecology is parasitic | |

| Edibility is inedible | |

Ganoderma applanatum (the artist's bracket, artist's conk,[1] artist's fungus or bear bread) is a bracket fungus with a cosmopolitan distribution.

Description

[edit]Ganoderma applanatum is parasitic and saprophytic,[2] and grows as a mycelium within the wood of living and dead trees. It grows in single, scattered, or compound formations.[2] It forms fruiting bodies that are 3–30 centimetres (1–12 inches) wide, 5–50 cm (2–19+1⁄2 in) long and 1–10 cm (1⁄2–4 in) thick,[1] hard as leather, and woody-textured.[3] They are white at first but soon turn dark red-brown. The upper surface of the fruiting body is covered with reddish brown conidia.

The fruiting bodies are perennial, and may persist for multiple years, increasing in size and forming new layers of pores as they grow. These layers can be distinguished in a cross section or from observation of the concentric rings on the upper surface of the fruiting body.[4] This allows the fruiting body's age to be determined using the same method as tree rings.[citation needed]

Brown spores are released from the pores on the underside of the fruiting body. The spores are highly concentrated, and as many as 4.65 billion spores can be dispersed from a 10 cm (4 in) by 10 cm section of the conk within 24 hours.[5] The tubes are 4–12 millimetres (1⁄8–1⁄2 in) deep and terminate in pores that are round with 4–6 per millimetre.[1]

Similar species

[edit]The similar Ganoderma brownii has thicker, darker flesh, often a yellow pore surface, and larger spores than G. applanatum.[1] G. oregonense, G. lucidum,[2] and Fomitopsis pinicola are also similar.[6]

Ecology

[edit]G. applanatum is a wood-decay fungus, causing a rot of heartwood in a variety of trees. It can also grow as a pathogen of live sapwood, particularly on older trees that are sufficiently wet. It is a common cause of decay and death of beech and poplar, and less often of several other tree genera, including alder, apple, elm, buckeye and horse chestnut, maple, oak, live oak, walnut, willow, western hemlock, Douglas fir, old or sick olive tree, and spruce. G. applanatum grows more often on dead trees than living ones.[7]

There are anecdotal references of higher primates consuming this fungus for self-medication.[8][2] In her book Gorillas in the Mist (1983), Dian Fossey writes the following:

Still another special food (for the gorillas) is bracket fungus (Ganoderma applanatum)... The shelflike projection is difficult to break free, so younger animals often have to wrap their arms and legs awkwardly around a trunk and content themselves by only gnawing at the delicacy. Older animals who succeed in breaking the fungus loose have been observed carrying it several hundred feet from its source, all the while guarding it possessively from more dominant individuals' attempts to take it away. Both the scarcity of the fungus and the gorillas' liking of it cause many intragroup squabbles, a number of which are settled by the silverback, who simply takes the item of contention for himself.[9]

The midge Agathomyia wankowiczii lays its eggs on the fruiting body of the fungus, forming galls.[10] Female forked fungus beetles, Bolitotherus cornutus lay their eggs on the surface of the fruiting bodies and the larvae live inside of the fruiting bodies of G. applanatum and a few other bracket fungi.[11] Meanwhile, the fly Hirtodrosophila mycetophaga courts and mates entirely on the underside of dark fungi.[12]

Uses

[edit]

A peculiarity of this fungus lies in its use as a drawing medium for artists.[13] When the fresh white pore surface is rubbed or scratched with a sharp implement, dark brown tissue under the pores is revealed, resulting in visible lines and shading that become permanent once the fungus is dried. This practice is what gives G. applanatum its common name.[5][7]

G. applanatum is a medicinal farming crop that is used as a flavor enhancer in Asian cuisine. G. applanatum is non-digestible in its raw form,[2][3] but is considered edible when cooked.[citation needed] Hot herbal soups, or fermentation in lemon acid with onion is a common use for cooking with G. applanatum slices as an umami flavor enhancer in fermented foods. G. applanatum can also be used in tea.[citation needed]

G. applanatum has been used to produce amadou, even though Fomes fomentarius is most commonly associated with the production of amadou.[14] Amadou is a leathery, easily flammable material that is produced from different polypores, but can also be consist of similar material.[15] Amadou generally has three areas of use: fire making, medicinal,[16] and clothing,[17][15] however, it is mostly associated with fire making.[18][19]

Medicinal uses

[edit]Medicinal use of G. applanatum has been extensive over thousands of years.[20] In Chinese medicine this fungus has been used to treat rheumatic tuberculosis and esophageal carcinoma. It has also been used more commonly to resolve indigestion, relieve pain and reduce phlegm.[21] Further studies have shown that its medicinal qualities also include anti-tumor, anti-oxidation and as a regulator for body immunity.[20]

G. applanatum is known in Japan as kofuki-saru-no-koshikake (コフキサルノコシカケ),[22][23] literally meaning "powder-covered monkey's bench", and in China as shu-she-ling-zhi (树舌灵芝), where it has long been used in traditional medicines.[24] Studies have shown G. applanatum contains compounds with potent anti-tumor,[25][26][27] antibacterial[28][29] anti-fibrotic[30] properties.

G. applanatum is generally studied from three angles: medicinal, phytopathological, and biotechnological.[31] Medicinal fungi such as G. applanatum are of special interest due to their antibiotic properties. Methanol extracts from G. applanatum have shown that the fatty acids present, such as palmitic acid, show antibacterial properties.[32] Compared to synthetic antibiotics these compounds extracted from G. applanatum lack problems of drug resistance and side effects.[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Ginns, James (2017). Polypores of British Columbia (Fungi: Basidiomycota). Victoria, BC: Province of British Columbia - Forests, Lands, and NR Operations. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7726-7053-3.

- ^ a b c d e Goldman, Gary B. (2019). Field Guide to Mushrooms & Other Fungi in South Africa. Marieka Gryzenhout. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Nature. ISBN 978-1-77584-654-3. OCLC 1117322804.

- ^ a b Meuninck, Jim (2017). Foraging Mushrooms Oregon: Finding, Identifying, and Preparing Edible Wild Mushrooms. Falcon Guides. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4930-2669-2.

- ^ Atkinson, George Francis (1901). Studies of American fungi. Mushrooms, edible, poisonous, etc. Ithaca, NY: Andrus & Church. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.120494.

- ^ a b "White Mottled Rot" (PDF). Fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ Davis, R. Michael; Sommer, Robert; Menge, John A. (2012). Field Guide to Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-520-95360-4. OCLC 797915861.

- ^ a b Biek, David (1984). The mushrooms of northern California. Redding, CA: Spore Prints. ISBN 0-9612020-0-9. OCLC 10870632.

- ^ COUSINS, Don; HUFFMAN, Michael A. (June 2002). "MEDICINAL PROPERTIES IN THE DIET OF GORILLAS" (PDF). African Study Monographs. 23 (2): 71. doi:10.14989/68214. S2CID 52244011.

- ^ Fossey, Dian (1983). Gorillas in the Mist. Mariner Books. p. 52. ISBN 9780395282175.

- ^ Brian Spooner; Peter Roberts (1 April 2005). Fungi. Collins. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-00-220152-0. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Liles, M.P. (1956). "A study of the life history of the forked fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus". Ohio J Sci. 56: 329–337. hdl:1811/4397/V56N06_329.pdf.

- ^ "The Evolutionary Biology of Colonizing Species - PDF Free Download". Epdf.pub. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ "Ganoderma applanatum: The Artist's Conk". The Fungal Kingdom. 2015-01-12. Archived from the original on 2015-01-12. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ Sundström, Lisa. "Fnöske - Naturhistoriska riksmuseet". Nrm.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ a b "fnöske | SAOB" (in Swedish). Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ Molitoris, H. P. (1994-04-01). "Mushrooms in medicine". Folia Microbiologica. 39 (2): 91–98. doi:10.1007/BF02906801. ISSN 1874-9356. PMID 7959435. S2CID 19354468.

- ^ Sundström, Lisa. "Fnösktickan, Fomes fomentarius, och dess användningsområden". Nrm.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "Göra eld med fnöske" (PDF). Bioresurs.uu.se. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2014.

- ^ Nationalencyklopedin 1991 (in Swedish). 1991. p. 450.

- ^ a b Elkhateeb, Waill A.; Zaghlol, Gihan M.; El-Garawani, Islam M.; Ahmed, Eman F.; Rateb, Mostafa E.; Abdel Moneim, Ahmed E. (2018-05-01). "Ganoderma applanatum secondary metabolites induced apoptosis through different pathways: In vivo and in vitro anticancer studies". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 101: 264–277. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.058. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 29494964. S2CID 4639322.

- ^ Moradali, Mohammad-Fata; Mostafavi, Hossien; Hejaroude, Ghorban-Ali; Tehrani, Abbas Sharifi; Abbasi, Mehrdad; Ghods, Shirin (2006). "Investigation of Potential Antibacterial Properties of Methanol Extracts from Fungus Ganoderma applanatum". Chemotherapy. 52 (5): 241–244. doi:10.1159/000094866. PMID 16899973. S2CID 24881421.

- ^ "kofuki- saru-no-koshikake (コフキサルノコシカケ)". Flora of Mikawa. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Mizuno, Takashi (1995). "Sarunokoshikake: Polyporaecea fungi-kofukisarunokoshikake, ganoderma applanatum and tsugasarunokoshikake, fomitopsis pinicola". Food Reviews International. 11: 129–133. doi:10.1080/87559129509541023.

- ^ "About Asian Anti-Cancer Materia Database". Asiancancerherb.info. Archived from the original on 2018-01-02. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ^ MIZUNO, TAKASHI; et al. "Isolation and characterization of antitumor active β-d-glucans from the fruit bodies of Ganoderma applanatum". Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam - Printed in The Netherlands. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Taichi Usui; et al. (2014). "Antitumor Activity of Water-Soluble β-D-Glucan Elaborated by Ganoderma applanatum". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 45: 323–326. doi:10.1080/00021369.1981.10864512.

- ^ Chairul; Tokuyama, Takashi; Hayashi, Yoshinori; Nishizawa, Mugio; Tokuda, Harukuni; Chairul, Sofni M.; Hayashi, Yuji (26 March 1991). "Applanoxidic acids A, B, C and D, biologically active tetracyclic triterpenes from Ganoderma applanatum". Phytochemistry. 30 (12): 4105–4109. Bibcode:1991PChem..30.4105C. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(91)83476-2.

- ^ Smania, Jr; Monache, Franco Delie; Smania, Elza de Fatima Albino; Cuneo, Rodrigo S. (1999). "Antibacterial Activity of Steroidal Compounds Isolated from Ganoderma applanatum". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 1, 1999 Issue 4 (4): 325–330. doi:10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v1.i4.40.

- ^ Osińska-Jaroszuk, Monika; Jaszek, Magdalena; Mizerska-Dudka, Magdalena; Błachowicz, Adriana; Rejczak, Tomasz Piotr; Janusz, Grzegorz; Wydrych, Jerzy; Polak, Jolanta; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, Anna; Kandefer-Szerszeń, Martyna (July 2014). "Exopolysaccharide from Ganoderma applanatum as a Promising Bioactive Compound with Cytostatic and Antibacterial Properties". BioMed Research International. 2014: 743812. doi:10.1155/2014/743812. PMC 4120920. PMID 25114920.

- ^ Luo, Q; Di, L; Dai, WF; Lu, Q; Yan, YM; Yang, ZL; Li, RT; Cheng, YX (February 23, 2015). "Applanatumin A, a new dimeric meroterpenoid from Ganoderma applanatum that displays potent antifibrotic activity". Org. Lett. 17 (5): 1110–3. doi:10.1021/ol503610b. PMID 25706347.

- ^ Ćilerdžić, Jasmina; Stajić, Mirjana; Vukojević, Jelena (2016-10-01). "Degradation of wheat straw and oak sawdust by Ganoderma applanatum". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 114: 39–44. Bibcode:2016IBiBi.114...39C. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2016.05.024. ISSN 0964-8305.

- ^ a b Moradali M, -F, Mostafavi H, Hejaroude G, -A, Tehrani A, S, Abbasi M, Ghods S: Investigation of Potential Antibacterial Properties of Methanol Extracts from Fungus <i>Ganoderma applanatum</i>. Chemotherapy 2006;52:241-244. doi: 10.1159/000094866

External links

[edit] Media related to Ganoderma applanatum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ganoderma applanatum at Wikimedia Commons- Phillips, D. H., & Burdekin, D. A. (1992). Diseases of Forest and Ornamental Trees. Macmillan.

- Ganoderma applanatum Archived 2012-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Ganoderma applanatum

- Photographs of the fungus, including one used as a drawing surface

- Several drawings created on these fungi Archived 2015-02-02 at the Wayback Machine