Map Snapshot

694 Records

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Brown creeper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Philadelphia, PA | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Certhiidae |

| Genus: | Certhia |

| Species: | C. americana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Certhia americana Bonaparte, 1838

| |

| |

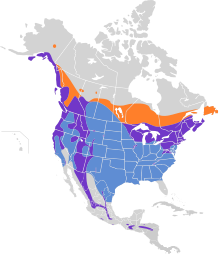

Breeding Year-round Nonbreeding

| |

The brown creeper (Certhia americana), also known as the American treecreeper, is a small songbird, the only North American member of the treecreeper family Certhiidae.

Description

[edit]Adults are brown on the upper parts with light spotting, resembling a piece of tree bark, with white underparts. They have a long thin bill with a slight downward curve and a long stiff tail used for support as the bird creeps upwards. The male creeper has a slightly larger bill than the female. Brown creepers are smaller than white-breasted nuthatches but larger than golden-crowned kinglets.[2]

Measurements:[3]

- Length: 4.7–5.5 in (12–14 cm)

- Weight: 0.2–0.3 oz (5.7–8.5 g)

- Wingspan: 6.7–7.9 in (17–20 cm)

Its voice includes single very high pitched, short, often insistent, piercing calls; see, or swee. The song often has a cadence like; pee pee willow wee or see tidle swee, with notes similar to the calls. Creepers in California have songs of four to nine syllables, except in the San Bernardino Mountains, where there are as many as nine to thirteen syllables per song, but within the same two second time frame.[4]

This species's avoidance of edges, cryptic plumage, and high-pitched vocalizations contribute to a low survey detection rate compared to other species.[5]

Distribution, habitat and range

[edit]Brown creepers are both migratory and year-round residents in North America. Their breeding habitat is mature forests, especially conifers, in Canada, Alaska and the northeastern and western United States, and they are non-breeding in the southern part of the United States. They are permanent residents through much of their range; many northern birds migrate to the southern half of the United States. Brown creepers have occurred as vagrants to Bermuda and Central America's mountains in Guatemala, Honduras and the northern cordillera of El Salvador. Since 1966 the brown creeper has experienced a yearly 1.5% population increase throughout the northeastern and northwestern (Pacific coast) regions of its range.[6] The first breeding brown creepers in the Northwest Territories were detected in 2008, in the Liard Valley, which may be a result of northern range expansion.[5]

As a migratory species with a northern range, this species is a conceivable vagrant to western Europe. However, it is intermediate in its characteristics between common treecreeper and short-toed treecreeper, and has sometimes in the past been considered a subspecies of the former, although its closest relative seems to be the latter (Tietze et al., 2006). Since the two European treecreepers are themselves among the most difficult species on that continent to distinguish from each other, a brown creeper would probably not even be suspected, other than on a treeless western island, and would be difficult to verify even then.

Brown creepers prefer mature, moist, coniferous forests or mixed coniferous/deciduous forests. They are found in drier forests as well, including Engelman Spruce and larch forest in eastern Washington. They generally avoid the rainforest of the outer coast. While they generally nest in hardwoods, conifers are preferred for foraging.

Breeding brown creepers generally require trees of a large diameter, whose deeper bark furrows support large amounts of bark-dwelling invertebrates such as spiders to make up a foraging substratum. They also require continual renewal of snags, with a preference for Balsam Fir in their New Brunswick breeding range.[7]

Brown creepers have been recorded breeding in the dry season (January–February) in Chalatenango Department, El Salvador, a behaviour unusual to insectivorous birds and shared in the region only by the golden-fronted woodpecker.[8]

Subspecies

[edit]Thirteen subspecies are recognised:[9]

- C. a. alascensis Webster, JD, 1986 – central south Alaska

- C. a. occidentalis Ridgway, 1882 – southeast Alaska, west Canada and west USA

- C. a. stewarti Webster, JD, 1986 – islands off British Columbia (southwest Canada)

- C. a. zelotes Osgood, 1901 – mountains of south Oregon to north, east, south California (west USA)

- C. a. phillipsi Unitt & Rea, 1997 – central California (west USA)

- C. a. montana Ridgway, 1882 – interior southwest Canada to central north and central USA

- C. a. leucosticta Van Rossem, 1931 – south Nevada and Utah (central west USA)

- C. a. americana Bonaparte, 1838 – south, east Canada and central north, northeast USA

- C. a. nigrescens Burleigh, 1935 – central east USA

- C. a. albescens Berlepsch, 1888 – southwest USA and northwest Mexico

- C. a. alticola Miller, GS, 1895 – west, southwest, central Mexico

- C. a. pernigra Griscom, 1935 – south Mexico and Guatemala

- C. a. extima Miller, W & Griscom, 1925 – east Guatemala to Nicaragua

Conservation status

[edit]

The species has declined in much of North America but appears to be doing well in Washington, with a small (not significant) increase on the state's breeding bird survey since 1966. As with many of Washington's birds, the Cascades divide this species into two subspecies.

In Wyoming, brown creepers have been recognized as preferring habitat within large, intact and mature stands of spruces, firs, or lodgepole pine. It is therefore potentially vulnerable to logging, climate change, or replacement of those tree species by Ponderosa pine.[10] However, it is not considered a species of serious concern in that state.[11]

In New Brunswick, brown creepers have been shown to respond negatively to even moderate forestry. Conservation efforts in the province have focused on maintaining unmanaged patches with high densities of trees and snags in mature forest.[7]

Ivory-billed woodcreepers (Xiphorhynchus flavigaster) have been observed extracting brown creeper nestlings and dropping them away from the nest.[8]

Behavior

[edit]Brown creepers forage on tree trunks and branches, typically zig-zagging upwards from the bottom of a tree trunk, and then flying down to the bottom of another tree. They creep slowly with their body flattened against the bark, probing with their beak for insects. They will rarely feed on the ground. They mainly eat small arthropods found in the bark, but sometimes they will eat seeds in winter.

Breeding

[edit]Breeding season typically begins in April. The female will make a partial cup nest either under a piece of bark partially detached from the tree, or in a tree cavity. It will lay 3–7 eggs, and incubation lasts approximately two weeks. Both of the parents help feed the chicks. Parents both take turns feeding nestlings and removing fecal sacs from the nest.[8]

Gallery

[edit]-

Toronto, Canada

-

A creeper at Great Falls, MD, USA

-

Brown creeper zig-zagging in Biddeford, ME

-

In Coastal Southern Alaska

-

In Ontario, Canada

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Certhia americana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22711244A94285552. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22711244A94285552.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Brown Creeper". All About Birds.

- ^ "Brown Creeper Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". All About Birds. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ Baptista, Luis F.; Krebs, Robin (2000). "Vocalizations and relationships of Brown Creepers Certhia americana: a taxonomic mystery". Ibis. 142 (3): 457–465. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2000.tb04442.x.

- ^ a b Olson, Cory R.; Hannah, Kevin C.; Gray, Christine (Autumn 2009). "First Confirmed Record of Breeding Brown Creepers in the Northwest Territories, Canada". Northwestern Naturalist. 90 (2): 156–159. doi:10.1898/NWN08-36.1. S2CID 84936362.

- ^ "Brown Creeper Certhia americana - BBS Trend Map, 1966 - 2015". USGS. US Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ a b Poulin, Jean-François; Villard, Marc-André; Edman, Mattias; Goulet, Pierre J.; Eriksson, Anna-Maria (April 2008). "Thresholds in nesting habitat requirements of an old forest specialist, the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana), as conservation targets". Biological Conservation. 141 (4): 1129–1137. Bibcode:2008BCons.141.1129P. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.02.012 – via Science Direct.

- ^ a b c Funes, Carlos; Bolaños, Oscar; Komar, Oliver (1 March 2012). "Breeding of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) in Central America". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 124 (1): 177–179. doi:10.1676/11-076.1. S2CID 83933957 – via BioOne Complete.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2023). "Nuthatches, Wallcreeper, treecreepers, mockingbirds, starlings, oxpeckers". IOC World Bird List Version 13.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Faulkner, Douglas W. (2010). Birds of Wyoming, p. 188. Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts and Company Publishers.

- ^ Wyoming Game and Fish Department (2017). State Wildlife Action Plan: Species of Greatest Conservation Need. https://wgfd.wyo.gov/WGFD/media/content/PDF/Habitat/SWAP/Wyoming-SGCN.pdf

Further reading

[edit]- Tietze, Dieter Thomas; Martens, Jochen & Sun, Yue-Hua (2006). "Molecular phylogeny of treecreepers (Certhia) detects hidden diversity". Ibis. 148 (3): 477–488. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00547.x.

- Thurber, Walter A. (1978). Cien Aves de El Salvador. San Salvador: Ministerio de Educación.

- Yurgenson A. : birds.cornell.edu

External links

[edit]- Brown Creeper - Certhia americana - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Brown Creeper - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Brown creeper species account - Animal diversity web

- "American Treecreeper media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Brown Creeper photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Certhia americana at IUCN Red List maps