Map Snapshot

99 Records

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Red-necked phalarope | |

|---|---|

| |

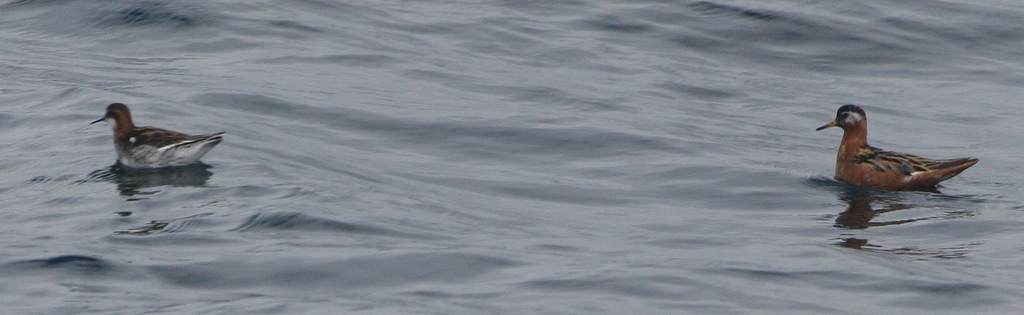

| Breeding plumage | |

| |

| Winter plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Phalaropus |

| Species: | P. lobatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phalaropus lobatus | |

| |

| Range of P. lobatus Breeding range Wintering range

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The red-necked phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus), also known as the northern phalarope and hyperborean phalarope,[2] is a small wader. This phalarope breeds in the Arctic regions of North America and Eurasia. It is migratory, and, unusually for a wader, winters at sea on tropical oceans.

Taxonomy

[edit]In 1743, the English naturalist George Edwards included an illustration and a description of the red-necked phalarope in the first volume of his A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. He used the English name "The coot-footed tringa". Edwards based his hand-coloured etching on a specimen that had been collected off the coast of Maryland.[3] When in 1758, the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae for the tenth edition, he placed the red-necked phalarope with the phalaropes and sandpipers in the genus Tringa. Linnaeus included a brief description, coined the binomial name Tringa lobata and cited Edwards' work.[4] The red-necked phalarope is now placed in the genus Phalaropus that was introduced by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760.[5][6] The English and genus names come through French phalarope and scientific Latin Phalaropus from Ancient Greek phalaris, "coot", and pous, "foot". Coots and phalaropes both have lobed toes. The specific lobatus is Neo-Latin for "lobed".[7][8] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[6]

Description

[edit]The red-necked phalarope is about 18 cm (7.1 in) in length, with lobed toes and a straight, fine bill. The breeding female is predominantly dark grey above, with a chestnut neck and upper breast, black face and white throat. They have a white wing stripe which helps distinguish this bird from the similar Wilson's phalarope. The breeding male is a duller version of the female. They have lobed toes to assist with their swimming. Young birds are grey and brown above, with buff underparts and a black patch through the eye. In winter, the plumage is essentially grey above and white below, but the black eyepatch is always present. They have a sharp call described as a whit or twit.

| Total Body Length | 170–200 mm (6.5–8 in) |

| Weight | 35 g (1.2 oz) |

| Wingspan | 380 mm (15 in) |

| Wing | 101–106.5 mm (4.0–4.2 in) |

| Tail | 45–51 mm (1.8–2.0 in) |

| Culmen | 20.2–23.5 mm (0.80–0.93 in) |

| Tarsus | 19.8–21.6 mm (0.78–0.85 in) |

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Breeding

[edit]

Female red-necked phalaropes are generally larger than males, though there is some overlap between small-bodied females and large-bodied males.[11] The females pursue and fight over males, and will defend their mate from other females until the clutch is complete and the male begins incubation.[12] The males perform all incubation and chick-rearing activities, while the females may attempt to find another mate.[12] Females may lay multiple clutches per year if her original nest fails or there are an excess of adult males in the breeding population.[13] Once it becomes too late in the breeding season to start new nests, females begin their southward migration, leaving the males to incubate the eggs and look after the young.[citation needed]

The nest is a grass-lined depression at the top of a small mound. Clutch size is usually four splotchy olive-buff eggs, but can be fewer. Incubation is about 20 days.[9] The young are precocial, and mainly feed themselves and are able to fly within 20 days of hatching.[14]

Feeding

[edit]When feeding, a red-necked phalarope will often swim in a small, rapid circle, forming a small whirlpool. This behaviour is thought to aid feeding by raising food from the bottom of shallow water. The bird will reach into the centre of the vortex with its bill, plucking small insects or crustaceans caught up therein. On the open ocean, they are often found where converging currents produce upwellings. During migration, some flocks stop over on the open waters at the mouth of the Bay of Fundy to take advantage of food stirred up by tidal action.

Migration

[edit]Almost all of the nonbreeding season is spent in open water. As this species rarely comes into contact with humans, it can be unusually tame.[citation needed]

Status

[edit]The red-necked phalarope is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies.

In Britain and Ireland

[edit]The red-necked phalarope is a rare and localised breeding species in Ireland and Britain, which lie on the extreme edge of its world range. The most reliable place for them is Shetland, particularly the Loch of Funzie on Fetlar, with a few birds breeding elsewhere in Scotland in the Outer Hebrides (e.g. at Loch na Muilne, where a "phalarope watchpoint" has been set up) and sometimes the Scottish Mainland in Ross-shire or Sutherland. They have also bred in western Ireland since about 1900, where the population reached a peak of about 50 pairs. There have been very few breeding records in Ireland since the 1970s, but breeding was reported from County Mayo in 2015, involving a male and three females.

The tracking of a tagged bird from Fetlar unexpectedly revealed that it wintered with a North American population in the tropical Pacific Ocean; it took a 16,000 mi (26,000 km) round trip across the Atlantic via Iceland and Greenland, then south down the Eastern seaboard of America, across the Caribbean and Mexico, before ending up off the coast of Ecuador and Peru. For this reason, it is suspected that the Shetland population could be an offshoot of a North American population rather than the geographically closer Scandinavian population that is believed to winter in the Arabian Sea.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2019). "Phalaropus lobatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22693490A155525960. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22693490A155525960.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Red-necked Phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus) - Avibase". avibase.bsc-eoc.org. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Edwards, George (1743). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Vol. Part 1. London: Printed for the author at the College of Physicians. p. 46, Plate 46.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 148. On page 148 Linnaeus spells the specific epithet as tobata. He corrects this to lobata on page 824.

- ^ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode Contenant la Division des Oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés (in French and Latin). Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 50, Vol. 6, p. 12.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Sandpipers, snipes, coursers". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ "Phalarope". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 229, 301. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b Godfrey, W. Earl (1966). The Birds of Canada. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada. p. 169.

- ^ Sibley, David Allen (2000). The Sibley Guide to Birds. New York: Knopf. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-679-45122-8.

- ^ Rubega, Margaret A. (1996). "Sexual Size Dimorphism in Red-necked Phalaropes and Functional Significance of Nonsexual Bill Structure Variation for Feeding Performance". Journal of Morphology. 228 (1): 45–60. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199604)228:1<45::AID-JMOR4>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 29852574.

- ^ a b Reynolds, John D. (1985). "Mating system and nesting biology of the Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus Zobatus: what constrains polyandry?". Ibis. 129: 225–242. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03203.x.

- ^ Hilden, Olavi; Vuolanto, Seppo (1972). "Breeding biology of the Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus in Finland". Ornis Fennica. 49: 57–85.

- ^ Reynolds, John D. (1985). "Philandering Phalaropes". Natural History. 8: 58–64.

- ^ Smith, Malcolm; Bolton, Mark; Okill, David J.; Summers, Ron W.; Ellis, Pete; Liechti, Felix; Wilson, Jeremy D. (2014). "Geolocator tagging reveals Pacific migration of Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus breeding in Scotland". Ibis. 156 (4): 870–873. doi:10.1111/ibi.12196.

Further reading

[edit]

- Hayman, Peter; Marchant, John; Prater, Tony (1986). Shorebirds: an identification guide to the waders of the world. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-60237-9.

- Bull, John; Farrand Jr., John (April 1984). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-41405-8.

- Reynolds, John D. (1987). "Mating system and nesting biology of the Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus: what constrains polyandry?". Ibis. 129 (Supplement S1): 225–242. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03203.x.

External links

[edit]- Red-necked phalarope - RSPB Birds by Name

- Red-necked Phalarope Image from Iceland at thomasoneil.com

- Red-necked phalarope at eNature.com

- BirdLife species factsheet for Phalaropus lobatus

- "Phalaropus lobatus". Avibase.

- "Red-necked phalarope media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Red-necked phalarope photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Phalaropus lobatus at IUCN Red List maps

- Red-necked phalarope - Phalaropus lobatus - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Audio recordings of Red-necked phalarope on Xeno-canto.

- Phalaropus lobatus in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr

- Red-necked phalarope media from ARKive