Map Snapshot

23 Records

Seasonality Snapshot

Source: Wikipedia

| Bolitotherus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Suborder: | Polyphaga |

| Infraorder: | Cucujiformia |

| Family: | Tenebrionidae |

| Genus: | Bolitotherus |

| Species: | B. cornutus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bolitotherus cornutus Panzer, 1794

| |

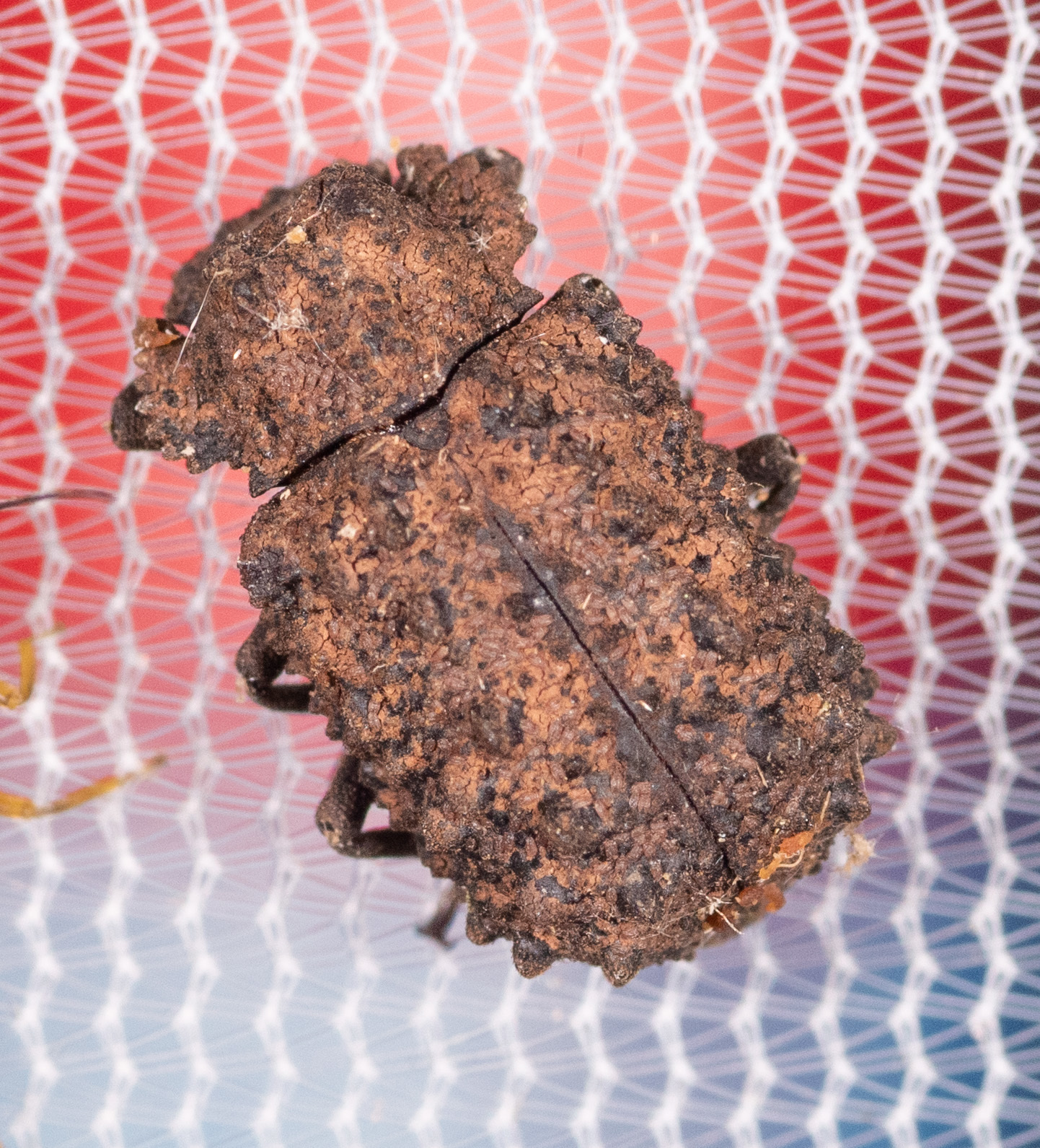

Bolitotherus cornutus is a North American species of darkling beetle known as the horned fungus beetle[1] or forked fungus beetle.[2] All of its life stages are associated with the fruiting bodies of a wood-decaying shelf fungus, commonly Ganoderma applanatum,[2] Ganoderma tsugae,[2] and Ganoderma lucidum.[3]

Description

[edit]Adults are brown, armored beetles, 10–12 mm (0.4–0.5 in) long.[1] They are sexually dimorphic; males have two sets of horns and females lack horns.[4] Males use their horns, clypeal and thoracic, to compete for mates. Unlike many species of scarab beetles that exhibit male dimorphism for horns with major and minor morphs,[5][6][7] male B. cornutus possess a continuous range of horn and body sizes.[8][9] Adult horned fungus beetles are active at night, but may be found during the day on the undersides of their host fungi.

Flight

[edit]The forked fungus beetle has the ability to fly; however, they are not at all reliant on flight.[10] The beetle itself is designed to be camouflaged onto bark or fungus, and so there is no advantage to frequent flights.

Habitat

[edit]The forked fungus beetle lives in a variety of climates. Due to the fact that the beetle consumes mainly shelf fungus of the Ganoderma family, they are restricted to areas in which Ganoderma fungus lives within North America.[11]

The beetle itself can live throughout these climates because they hibernate, or winter. Beetles of all developmental stages can winter but they tend to winter in different locations. Mature beetles can winter in bark, decaying trees, and stumps, among others. Both mature and immature beetles can also winter in fungus.[12]

Geographic range

[edit]Bolitherus cornutus tends to live in eastern North America. They do not have a strict climate preference, as they commonly live as north as Canada and as south as Florida.[5] The main requirement for where they will live correlates to where their preferred host fungus lives, and in turn the trees where the host fungus prefers to live.

Male territorial defense

[edit]The horned fungus beetle's entire life revolves around fungal brackets. Similarly to how a burying beetle needs a carcass to reproduce, horned fungus beetles need a fungal bracket to reproduce. Male beetles will find and defend a piece of fungus they deem to be good for offspring. Females are limited in how many offspring they can have by how big the fungus is, causing them to select males with larger pieces of fungi. This leads to male-male fighting over fungal brackets, as a male wants the largest fungus in order to attract females.[13]

Diet

[edit]The forked fungus beetle almost exclusively consumes the fungus of the Ganoderma family. Although adults can consume other materials, larvae prefer to only consume the egg that they hatched from and the fungus that they are raised within.[12]

Reproductive behavior

[edit]Oviposition

[edit]Unlike many darkling beetles, they tend to lay fewer eggs at a time, often only laying one egg per mate or even one egg per mating season. Their mating season usually lasts from June to August. The beetles very rarely lay more than one egg at a time, but on average can lay 8-12 eggs in a season. Eggs are only laid between June and August, which leads to a very limited number of offspring depending on how often females mate.[12]

Forked fungus beetle eggs are often laid in clutches of only one, but they can be laid in groups of egg capsules. These capsules are usually ovular in shape. They are usually 3.8 mm wide and 2.7 mm in width. The individual eggs within the capsule are translucent, approximately 2 mm long and 1mm wide. The eggs are white with raised darker spots.[12]

The eggs themselves can take anywhere between one and four weeks to hatch, but usually only take two. Post-hatching, the larvae take 5 days before they leave their egg capsules and go into the fungus they were laid upon.[12]

Mating

[edit]Bolitotherus cornutus adults perform reproductive behaviors on the surfaces of fruiting bodies of their host fungus.[8] Mating pairs engage in a courtship ritual in which the male grips the female's elytra, with his thorax over the end of her abdomen. Courtship often lasts several hours, and is a necessary precursor to copulation. During a copulation attempt, the male reverses position on top of the female so that both individuals point the same direction and their abdomens are aligned. If the courtship is successful, the female opens her anal sternite and copulation takes place. Following copulation, the male remains on top, facing the same direction as the female and mate-guards her. The male remains in this position for several hours, preventing other males from courting the female. Later, the female will deposit single eggs on the upper surface of a host fungus, then cover each egg with a distinctive dark brown oval of frass. When the eggs hatch, the larvae burrow into and consume the fungus, in which they later pupate before emerging as adults.[2]

-

A pair of in copula, attacked by a second male

-

Large male attacks a smaller male on top of a female

Mate searching behavior

[edit]For B. cornutus, males need to attract females. Females have the ability to selectively open and close their anal plate in order to entirely physically block males. This means that many males need to present themselves for female selection. Males can convince females to mate with them by having territorial control over large fungal brackets. Females need as much food as possible for their offspring, and so females are more likely to be attracted to males who have a larger fungus.[10]

Male age based competition

[edit]Age has a major effect on the sperm for the forked fungus beetle. As a male beetle ages, his sperm packet gets larger each time. It is not directly linked to each individual sperm packet being larger, but over time there is significant data. These larger sperm packets over time mean that older beetles are more likely to father offspring. This advantage specifically means that beetles that live the longest have the best chances of mating.[11]

Sexual selection

[edit]Horn length in male Bolitotherus cornutus is under significant direct selection. Females consistently select for longer horn lengths in male mates when given the opportunity. This positive selection on male horn length is mainly due to differences in the lifespan of male B. cornutus as well as concentration and access to females. Additionally, B. cornutus with longer horns on average also have longer elytral length, which are the hardened forewings of a beetle as well as bigger overall masses. As a result, all three of these traits result in positive total sexual selection amongst mating B. cornutus.[8]

Social behavior

[edit]Larval sociality and cannibalism

[edit]Larva often do not interact with their parents after hatching. Larva themselves are protected firstly by their egg capsules and then by the fungus they live and develop within when they hatch. Larva do not often interact with other larva, although larval passages and tunnels throughout the fungus often intersect.[12]

The pupal stage occurs after the larval stage. After create larval passages in the fungus, the larval will construct a pupal chamber in which it will mature. The larva will become less active as it becomes a pupa as it needs to enter this stage to mature into an adult beetle. This pupa is more prone to potential predators. Oftentimes, these pupa are attacked or consumed by larval siblings or by other forked fungus beetle larva. There is evidence of the larva potentially attacking and consuming one another, however, larval cannibalism of pupa has been experimentally observed.[12]

Once the pupa has matured into an adult beetle, the socialization between individuals of this species diminishes until reproduction.[12]

Life cycle

[edit]Forked fungus beetles are divided into two different brood groups for development. It is affected by when in the year the eggs are laid.[12]

For the first brood, the eggs are laid in June. They take approximately 2 weeks to hatch. Their larval stage can also take approximately 2 weeks. Then, their pupal stage can take approximately two months as they enter winter. The first brood spends their first winter as adults.[12]

For the secondary brood, eggs are laid in July and take longer on average to hatch than the first brood. Because of how late in the season the second brood hatches, they oftentimes winter in their larval stage. This means that they hibernate and slow their development during this time. They continue development again in the summer. Once they are done wintering, their pupal stage is shorter than the first brood's. Development for the forked fungus beetle is the quickest during early summer. The secondary brood becomes adults in their second summer and oftentimes can then reproduce within the same summer.[12]

Regardless of brood, the earliest they can reproduce is their second summer. However, the first brood tends to reproduce in the early summer and their offspring are more likely to be first brood. The second brood are usually not sexually mature until the end of their second summer, and so they are more likely to have second brood offspring.[12]

Forked fungus beetles can live up to 8 years, and so the pattern of first brood parents having first brood offspring, and second brood offspring have second brood offspring is unconfirmed and unstudied past their first reproductive season.[12]

Predators

[edit]B. cornutus has many predators. The majority of the fungus beetle's defenses are designed to fight against other members of the same species for reproductive purposes.

Mammalian

[edit]Due to the stationary nature of their life, it is also incredibly common for mammals to both purposefully and accidentally try to consume them. Rodents often predate on the beetle, ranging from small pocket mice to even large ground squirrels.[14]

Insect

[edit]The Eubadizon orchesiae, a braconid wasp, is a parasitic wasp that persists off of the eggs of the forked fungus beetle.[12] Female braconid wasps often find early-stage egg capsules of the forked fungus beetle and burrow a small hole within it in order to lay their eggs inside. They make a light yellow silken cocoon in the body of the larva.[2] However, they would also lay eggs within cracks and crevices of the fungal shelves the eggs were on as well. The wasps have a shorter gestation period than the forked fungus beetle, and so the larva of the braconid wasp will often consume the unhatched eggs or the larva of the forked fungus beetle. However, adult female braconid wasps themselves will often attack larva of the forked fungus beetle.[12]

Fungal

[edit]Some larvae die after attack by an uncharacterized parasitic fungus. Fomes applanatus is a fungus that often overtakes the fungal shelves that the forked fungus beetles lay their eggs upon.[12] The fungus itself will consume egg capsules as well as larva of the forked fungus beetle.

Defenses

[edit]The fungus beetle has three major defenses against these predators. The fungus beetle itself is camouflaged to fit into the fungus that it lives in. The rough texture and dark color often help the beetle blend into both the bark of the trees the fungus attached to as well as the fungus itself. Furthermore, the beetle's exoskeleton is quite hard and makes it difficult to puncture and attack the beetle. The most complex form of defense the beetle has is a chemical defense. B. Cornutus has the ability to detect mammalian breathe, and in response they can produce a volatile gas. This volatile gas can be produced by any mature forked fungus beetle, but their diet can affect the exact makeup of the gas.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Evans, Arthur V. (2014). Beetles of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691133041.

- ^ a b c d e Liles, M.P. (1956). "A study of the life history of the forked fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus". Ohio J Sci. 56: 329–337. hdl:1811/4397.

- ^ Heatwole, H.; Heatwole, A. (1 January 1968). "Movements, Host-Fungus Preferences, and Longevity of Bolitotherus cornutus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 61 (1): 18–23. doi:10.1093/aesa/61.1.18.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a scholarly publication published under a copyright license that allows anyone to reuse, revise, remix and redistribute the materials in any form for any purpose:

This article incorporates text from a scholarly publication published under a copyright license that allows anyone to reuse, revise, remix and redistribute the materials in any form for any purpose:

Benowitz, K. M.; Brodie, E. D.; Formica, V. A. (2012). Proulx, Stephen R (ed.). "Morphological Correlates of a Combat Performance Trait in the Forked Fungus Beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e42738. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...742738B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042738. PMC 3419742. PMID 22916153. Please check the source for the exact licensing terms. - ^ a b Lailvaux, S. P.; Hathway, J.; Pomfret, J.; Knell, R. J. (2005). "Horn size predicts physical performance in the beetle Euoniticellus intermedius (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)". Functional Ecology. 19 (4): 632. Bibcode:2005FuEco..19..632L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2005.01024.x.

- ^ Emlen DJ (1996) Artificial selection on horn length body size allometry in the horned beetle Onthophagus acuminatus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Evolution 50: 1219–1230. doi:10.2307/2410662

- ^ Emlen, D. J.; Corley Lavine, L.; Ewen-Campen, B. (2007). "Colloquium Papers: On the origin and evolutionary diversification of beetle horns". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (Suppl 1): 8661–8668. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8661E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701209104. PMC 1876444. PMID 17494751.

- ^ a b c Conner JK (1988) Field measurements of natural and sexual selection in the fungus beetle, Bolitotherus cornutus. Evolution 42: 736–749. doi:10.2307/2408865.

- ^ Formica, V. A.; McGlothlin, J. W.; Wood, C. W.; Augat, M. E.; Butterfield, R. E.; Barnard, M. E.; Brodie Iii, E. D. (2011). "Phenotypic Assortment Mediates the Effect of Social Selection in a Wild Beetle Population". Evolution. 65 (10): 2771–2781. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01340.x. PMID 21967420.

- ^ a b Orlander, Evelyne. "Bolitotherus cornutus". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ a b c Conner, Jeffrey; Camazine, Scott; Aneshansley, Daniel; Eisner, Thomas (1985-01-01). "Mammalian breath: trigger of defensive chemical response in a tenebrionid beetle (Bolitotherus cornutus)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 16 (2): 115–118. doi:10.1007/BF00295144. ISSN 1432-0762. S2CID 35130398.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Liles, M. Pferrer. "A STUDY OF THE LIFE HISTORY OF THE FORKED FUNGUS BEETLE, BOLITOTHERUS CORNUTUS (PANZER)".

- ^ "forked fungus beetle - Bolitotherus cornutus". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Parmenter, Robert (April 1, 1988). "Factors Limiting Populations of Arid-Land Darkling Beetles (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): Predation by Rodents". academic.oup.com. Retrieved March 1, 2024.